Joachim Von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop - 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

In 1928, Ribbentrop was introduced to Adolf Hitler as a businessman with foreign connections who "gets the same price for German champagne as others get for French champagne". Wolf-Heinrich Graf von Helldorff, with whom Ribbentrop had served in the 12th Torgau Hussars in the First World War, arranged the introduction. Ribbentrop and his wife joined the Nazi Party on 1 May 1932. Ribbentrop began his political career by offering to be a secret emissary between Chancellor of Germany Franz von Papen, his old wartime friend, and Hitler. His offer was initially refused. Six months later, however, Hitler and Papen accepted his help.

Their change of heart occurred after General Kurt von Schleicher ousted Papen in December 1932. This led to a complex set of intrigues in which Papen and various friends of president Paul von Hindenburg negotiated with Hitler to oust Schleicher. On 22 January 1933, State Secretary Otto Meissner and Hindenburg's son Oskar met Hitler, Hermann Göring, and Wilhelm Frick at Ribbentrop's home in Berlin's exclusive Dahlem district. Over dinner, Papen made the fateful concession that if Schleicher's government were to fall, he would abandon his demand for the Chancellorship and instead use his influence with President Hindenburg to ensure Hitler got the Chancellorship.

Ribbentrop was not popular with the Nazi Party's Alte Kämpfer (Old Fighters); they nearly all disliked him. British historian Laurence Rees described Ribbentrop as "the Nazi almost all the other leading Nazis hated". Joseph Goebbels expressed a common view when he confided to his diary that "Von Ribbentrop bought his name, he married his money and he swindled his way into office". Ribbentrop was among the few who could meet with Hitler at any time without an appointment, however, unlike Goebbels or Göring.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler's notice as a well-travelled businessman with more knowledge of the outside world than most senior Nazis and as a perceived authority on foreign affairs. He offered his house Schloss Fuschl for the secret meetings in January 1933 that resulted in Hitler's appointment as Chancellor of Germany. He became a close confidant of Hitler, to the disgust of some party members, who thought him superficial and lacking in talent. He was appointed ambassador to the Court of St James's, the royal court of the United Kingdom, in 1936 and then Foreign Minister of Germany in February 1938.

Ribbentrop became Hitler's favourite foreign-policy adviser, partly by dint of his familiarity with the world outside Germany but also by flattery and sycophancy. One German diplomat later recalled, "Ribbentrop didn't understand anything about foreign policy. His sole wish was to please Hitler". In particular, Ribbentrop acquired the habit of listening carefully to what Hitler was saying, memorizing his pet ideas and then later presenting Hitler's ideas as his own, a practice that much impressed Hitler as proving Ribbentrop was an ideal Nazi diplomat.Ribbentrop quickly learned that Hitler always favoured the most radical solution to any problem and accordingly tendered his advice in that direction as a Ribbentrop aide recalled:

When Hitler said "Grey", Ribbentrop said "Black, black, black". He always said it three times more, and he was always more radical. I listened to what Hitler said one day when Ribbentrop wasn't present: "With Ribbentrop it is so easy, he is always so radical. Meanwhile, all the other people I have, they come here, they have problems, they are afraid, they think we should take care and then I have to blow them up, to get strong. And Ribbentrop was blowing up the whole day and I had to do nothing. I had a break – much better!"

Ambassador to the United Kingdom

In August 1936, Hitler appointed Ribbentrop ambassador to the United Kingdom with orders to negotiate an Anglo-German alliance. Ribbentrop arrived to take up his position in October 1936. Ribbentrop's time in London was marked by an endless series of social gaffes and blunders that worsened his already-poor relations with the British Foreign Office.

Invited to stay as a house guest of the 7th Marquess of Londonderry at Wynyard Hall in County Durham, in November 1936, he was taken to a service in Durham Cathedral, and the hymn Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken was announced. As the organ played the opening bars, identical to the German national anthem, Ribbentrop gave the Nazi salute and had to be restrained by his host.

At his wife's suggestion, Ribbentrop hired the Berlin interior decorator Martin Luther to assist with his move to London and help realise the design of the new German embassy that Ribbentrop had built there (he felt that the existing embassy was insufficiently grand). Luther proved to be a master intriguer and became Ribbentrop's favourite hatchet man.

Martin Luther - Interior decorator!

He participated in the January 1942 Wannsee Conference, at which the genocidal Final Solution to the Jewish Question was planned; it was the 1947 discovery of his copy of the minutes that first made the Allied powers aware that the conference had taken place and what its purpose was.

Ribbentrop chose to spend as little time as possible in London to stay close to Hitler, which irritated the British Foreign Office immensely, as Ribbentrop's frequent absences prevented the handling of many routine diplomatic matters. (Punch referred to him as the "Wandering Aryan" for his frequent trips home.) As Ribbentrop alienated more and more people in Britain, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring warned Hitler that Ribbentrop was a "stupid ass". Hitler dismissed Göring's concerns: "But after all, he knows quite a lot of important people in England." That remark led Göring to reply "Mein Führer, that may be right, but the bad thing is, they know him"

n February 1937, Ribbentrop committed a notable social gaffe by unexpectedly greeting George VI with the "German greeting", a stiff-armed Nazi salute: the gesture nearly knocked over the King, who was walking forward to shake Ribbentrop's hand at the time. Ribbentrop further compounded the damage to his image and caused a minor crisis in Anglo-German relations by insisting that henceforward all German diplomats were to greet heads of state by giving and receiving the stiff-arm fascist salute. The crisis was resolved when Neurath pointed out to Hitler that under Ribbentrop's rule, if the Soviet ambassador were to give the Communist clenched-fist salute, Hitler would be obliged to return it. On Neurath's advice, Hitler disavowed Ribbentrop's demand that King George receive and give the "German greeting".

Ribbentrop had also negotiated the Anti-Comintern Pact with Japan (1936) and, after his appointment as minister of foreign affairs in February 1938, he signed the “Pact of Steel” with Italy (May 22, 1939), linking Europe’s two most aggressive fascist dictatorships in an alliance in case of war. Ribbentrop’s greatest diplomatic coup, however, was the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact of Aug. 23, 1939, which cleared the way for Hitler’s attack on Poland on Sept. 1, 1939, thus beginning World War II.

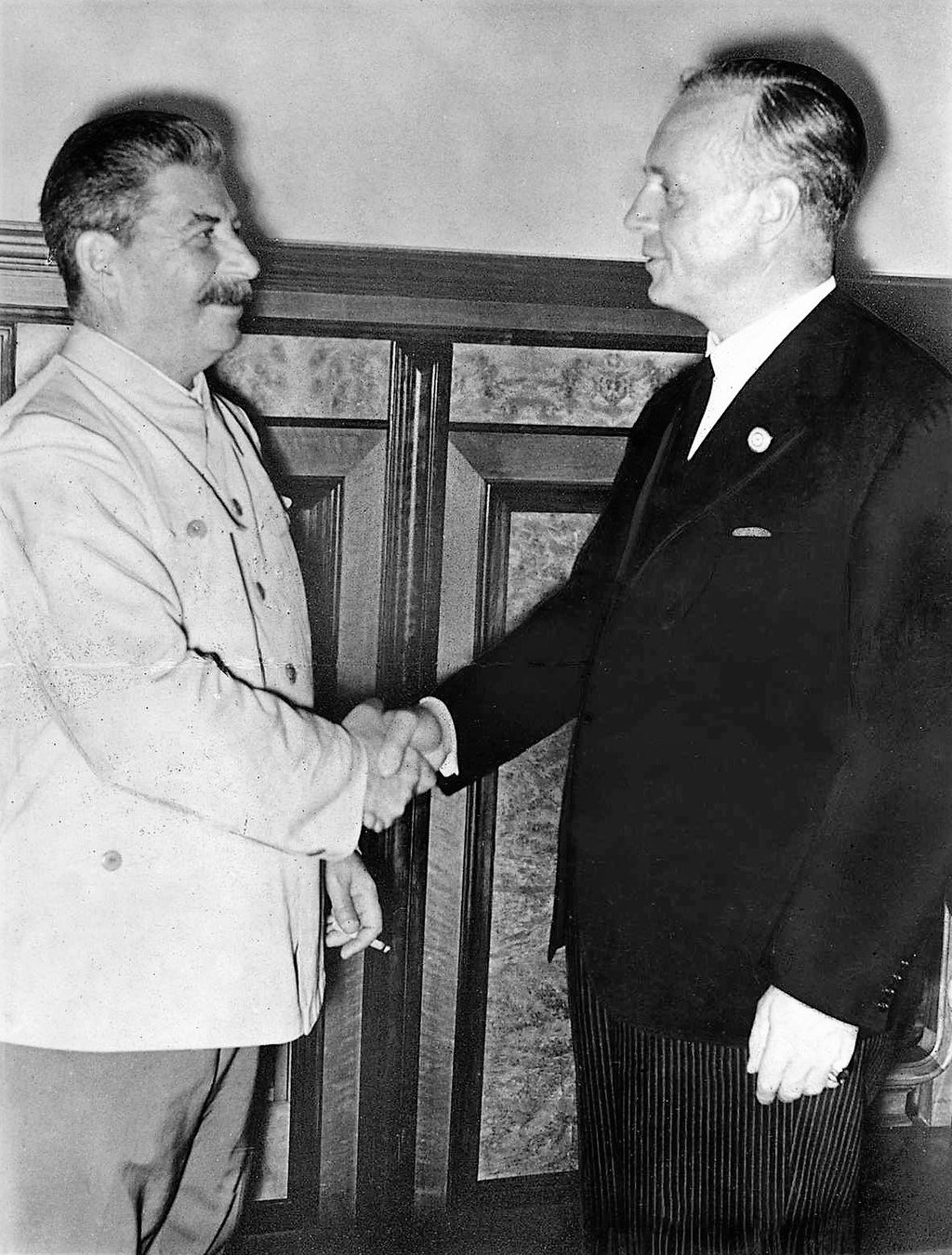

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that partitioned Eastern Europe between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov

Stalin and Ribbentrop at the signing of the Non-Aggression Pact, 23 August 1939

The Pact of Steel (German: Stahlpakt, Italian: Patto d'Acciaio), formally known as the Pact of Friendship and Alliance between Germany and Italy, was a military and political alliance between Italy and Germany.signed on 22 May 1939 by foreign ministers Galeazzo Ciano of Italy and Joachim von Ribbentrop of Germany.

Ribbentrop the Merchant of War

Ribbentrop spent the last weeks of September 1938 looking forward very much to the German-Czechoslovak war that he expected to break out on 1 October 1938. Ribbentrop regarded the Munich Agreement as a diplomatic defeat for Germany, as it deprived Germany of the opportunity to wage the war to destroy Czechoslovakia that Ribbentrop wanted to see. The Sudetenland issue, which was the ostensible subject of the German-Czechoslovak dispute, had been a pretext for German aggression. During the Munich Conference, Ribbentrop spent much of his time brooding unhappily in the corners. Ribbentrop told the head of Hitler's Press Office, Fritz Hesse, that the Munich Agreement was "first-class stupidity.... All it means is that we have to fight the English in a year, when they will be better armed.... It would have been much better if war had come now". Like Hitler, Ribbentrop was determined that in the next crisis, Germany would not have its professed demands met in another Munich-type summit and that the next crisis to be caused by Germany would result in the war that Chamberlain had "cheated" the Germans out of at Munich.

On 27 August 1939, Chamberlain sent a letter to Hitler that was intended to counteract reports Chamberlain had heard from intelligence sources in Berlin that Ribbentrop had convinced Hitler that the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact would ensure that Britain would abandon Poland. In his letter, Chamberlain wrote:

Whatever may prove to be the nature of the German-Soviet Agreement, it cannot alter Great Britain's obligation to Poland which His Majesty's Government have stated in public repeatedly and plainly and which they are determined to fulfil.

It has been alleged that, if His Majesty's Government had made their position more clear in 1914, the great catastrophe would have been avoided. Whether or not there is any force in that allegation, His Majesty's Government are resolved that on this occasion there shall be no such tragic misunderstanding.

If the case should arise, they are resolved, and prepared, to employ without delay all the forces at their command, and it is impossible to foresee the end of hostilities once engaged. It would be a dangerous illusion to think that, if war once starts, it will come to an early end even if a success on any one of the several fronts on which it will be engaged should have been secured.

Declining influence

As the war went on, Ribbentrop's influence waned. Because most of the world was at war with Germany, the Foreign Ministry's importance diminished as the value of diplomacy became limited. By January 1944, Germany had diplomatic relations only with Argentina, Ireland, Vichy France, the Italian Social Republic in Italy, Occupied Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Croatia, Bulgaria, Switzerland, the Holy See, Spain, Portugal, Turkey, Thailand, Japan, and the Japanese puppet states of Manchukuo and the Wang Jingwei regime in China. Later that year, Argentina and Turkey severed ties with Germany; Romania and Bulgaria joined the Allies and Finland made a separate peace with the Soviet Union and declared war on Germany.

Hitler found Ribbentrop increasingly tiresome and started to avoid him. The Foreign Minister's pleas for permission to seek peace with at least some of Germany's enemies—the Soviet Union in particular—played a role in their estrangement. As his influence declined, Ribbentrop spent his time feuding with other Nazi leaders over control of antisemitic policies to curry Hitler's favour.

Ribbentrop suffered a major blow when many old Foreign Office diplomats participated in the 20 July 1944 putsch and assassination attempt on Hitler. Ribbentrop had not known of the plot, but the participation of so many current and former Foreign Ministry members reflected badly on him. Hitler felt that Ribbentrop's "bloated administration" prevented him from keeping proper tabs on his diplomats' activities. Ribbentrop worked closely with the SS, with which he had reconciled, to purge the Foreign Office of those involved in the putsch.[267] In the hours immediately following the assassination attempt on Hitler, Ribbentrop, Göring, Dönitz, and Mussolini were having tea with Hitler in Rastenberg when Dönitz began to rail against the failures of the Luftwaffe. Göring immediately turned the direction of the conversation to Ribbentrop, and the bankruptcy of Germany's foreign policy. "You dirty little champagne salesman! Shut your mouth!" Göring shouted, threatening to smack Ribbentrop with his marshal's baton. But Ribbentrop refused to remain silent at this disrespect. "I am still the Foreign Minister," he shouted, "and my name is von Ribbentrop!"

On 20 April 1945, Ribbentrop attended Hitler's 56th birthday party in Berlin.[269] Three days later, Ribbentrop attempted to meet Hitler, but was rejected with the explanation the Führer had more important things to do.

Arrest

After Hitler's suicide, Ribbentrop attempted to find a role under the new president, Karl Dönitz, but was rebuffed. He went into hiding under an assumed name (Herr Reiser) in the port city of Hamburg. On 14 June, after Germany's surrender, Ribbentrop was arrested by Sergeant Jacques Goffinet, a French citizen who had joined the 5th Special Air Service, the Belgian SAS, and was working with the British Army near Hamburg. He was found with a rambling letter addressed to the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill criticizing British foreign policy for anti-German sentiments, and blaming Britain's failure to ally with Germany before the war for the Soviet occupation of eastern Germany and the advancement of Bolshevism into central Europe.

Trial and execution

Ribbentrop was a defendant at the Nuremberg trials. The Allies' International Military Tribunal convicted him on four counts: crimes against peace, deliberately planning a war of aggression, committing war crimes, and crimes against humanity. According to the judgment, Ribbentrop was actively involved in planning the Anschluss, as well as the invasions of Czechoslovakia and Poland. He was also deeply involved in the "final solution"; as early as 1942 he had ordered German diplomats in Axis countries to hasten the process of sending Jews to death camps in the east. Ribbentrop claimed that Hitler made all the important decisions himself, and that he had been deceived by Hitler's repeated claims of only wanting peace. The Tribunal rejected this argument, saying that given how closely involved Ribbentrop was with the execution of the war, "he could not have remained unaware of the aggressive nature of Hitler's actions." Even in prison, Ribbentrop still remained loyal to Hitler: "Even with all I know, if in this cell Hitler should come to me and say 'do this!', I would still do it."

Ribbentrop in his cell at Nuremberg after the trials had concluded.

On 16 October 1946, Ribbentrop became the first of those sentenced to death at Nuremberg to be hanged, after Göring committed suicide just before his scheduled execution. The hangman was U.S. Master Sergeant John C. Woods. Ribbentrop was escorted up the 13 steps of the gallows and asked if he had any final words. He said: "God protect Germany. God have mercy on my soul. My final wish is that Germany should recover her unity and that, for the sake of peace, there should be understanding between East and West. I wish peace to the world." Nuremberg Prison Commandant Burton C. Andrus later recalled that Ribbentrop turned to the prison's Lutheran chaplain, Henry F. Gerecke, immediately before the hood was placed over his head and then he whispered, "I'll see you again." His body, like those of the other nine executed men and of the suicide Hermann Göring, was cremated at Ostfriedhof (Munich) and his ashes were scattered in the river Isar.

Ribbentrop's body after his execution

Ribbentrop's detention report and mugshots

Born 30 April 1893

Wesel, Kingdom of Prussia, German Empire

Died16 October 1946 (aged 53)

Nuremberg Prison, Nuremberg, Allied-occupied Germany

Ribbentrop Documentary made by the excellent Peoples profiles