"I will leap into my grave laughing because the feeling that I have five million human beings on my conscience is for me a source of extraordinary satisfaction"

The extraordinary life of

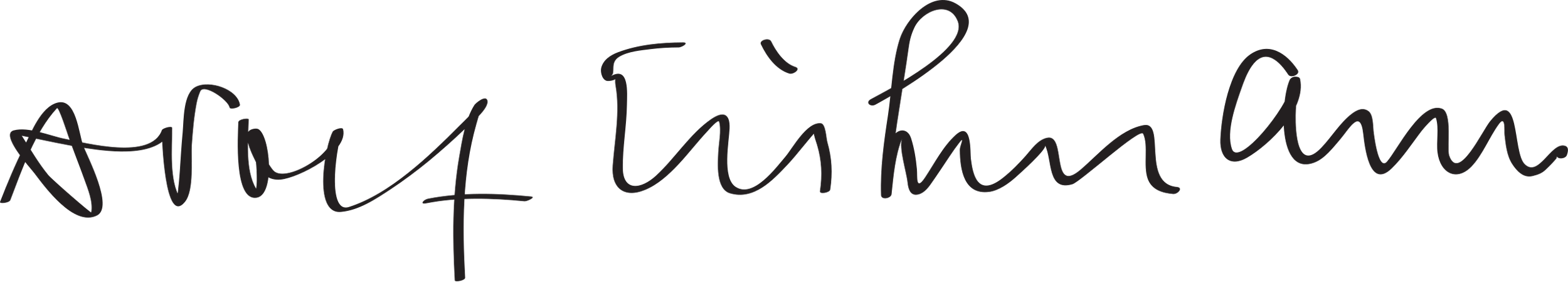

Adolf Eichmann

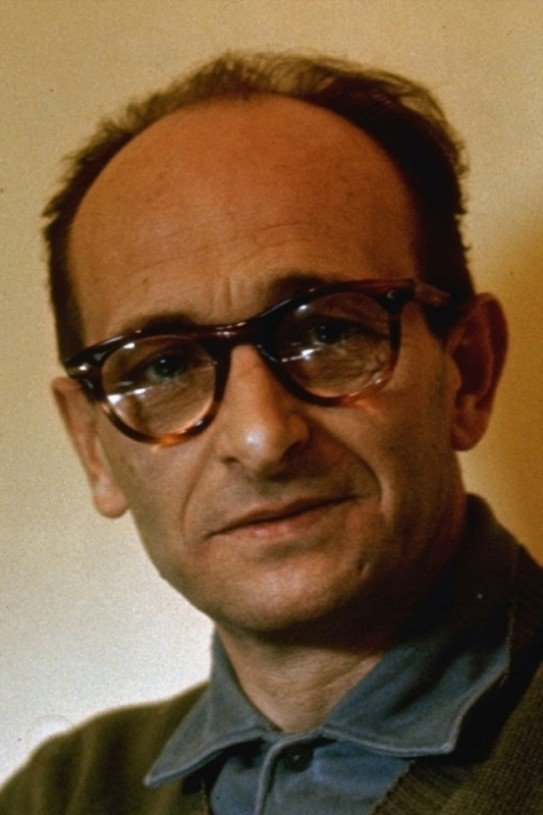

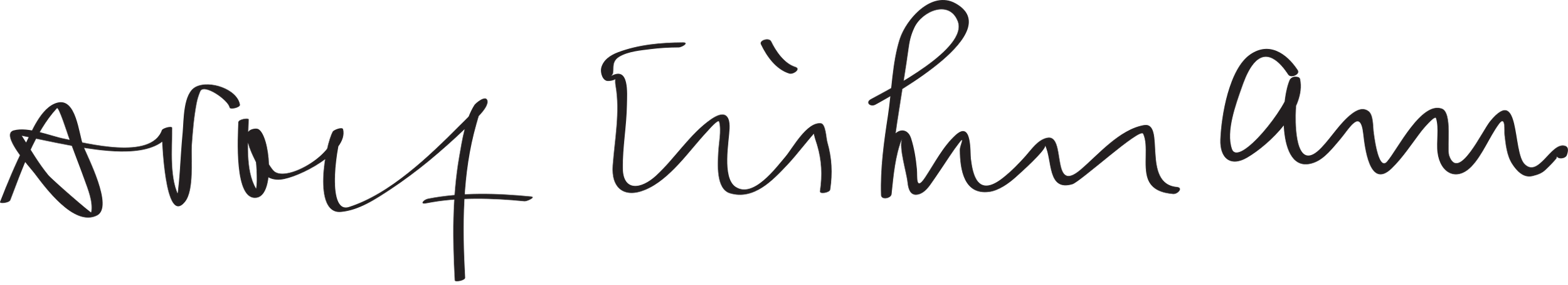

Otto Adolf Eichmann (19 March 1906 – 1 June 1962) was a German-Austrian official of the Nazi Party, an officer of the Schutzstaffel (SS), and one of the major organisers of the Holocaust. He participated in the January 1942 Wannsee Conference, at which the implementation of the genocidal Final Solution to the Jewish Question was planned. Following this, he was tasked by SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich with facilitating and managing the logistics involved in the mass deportation of millions of Jews to Nazi ghettos and Nazi extermination camps across German-occupied Europe. He was captured and detained by the Allies in 1945, but escaped and eventually settled in Argentina. In May 1960, he was abducted by Mossad, the national intelligence agency of Israel. Eichmann subsequently stood trial with the Supreme Court of Israel. The highly publicised Eichmann trial resulted in his conviction in Jerusalem, following which he was executed by hanging in 1962.

Early Life

Otto Adolf Eichmann, the eldest of five children, was born in 1906 to a Calvinist Protestant family in Solingen, Germany. His parents were Adolf Karl Eichmann, a bookkeeper, and Maria (née Schefferling), a housewife. The elder Adolf moved to Linz, Austria, in 1913 to take a position as commercial manager for the Linz Tramway and Electrical Company, and the rest of the family followed a year later. After the death of Maria in 1916, Eichmann's father married Maria Zawrzel, a devout Protestant with two sons.

Eichmann attended the Kaiser Franz Joseph Staatsoberrealschule (state secondary school) in Linz, the same high school Adolf Hitler had attended 17 years before. He played the violin and participated in sports and clubs, including a Wandervogel woodcraft and scouting group that included some older boys who were members of various right-wing militias. His poor school performance resulted in his father's withdrawing him from the Realschule and enrolling him in the Höhere Bundeslehranstalt für Elektrotechnik, Maschinenbau und Hochbau vocational college. He left without attaining a degree and joined his father's new enterprise, the Untersberg Mining Company, where he worked for several months. Eichmann then went onto work in Upper Austria and Salzburg as district agent for the Vacuum Oil Company AG.

During this time, he joined the Jungfrontkämpfervereinigung, the youth section of Hermann Hiltl's right-wing veterans movement, and began reading newspapers published by the Nazi Party. The party platform included the dissolution of the Weimar Republic in Germany, rejection of the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, radical antisemitism, and anti-Bolshevism. They promised a strong central government, increased Lebensraum (living space) for Germanic peoples, formation of a national community based on race, and racial cleansing via the active suppression of Jews, who would be stripped of their citizenship and civil rights.

Kaiser Franz Joseph Staatsoberrealschule

Kaiser Franz Joseph Staatsoberrealschule, Notable alumni

Adolf Eichmann (1906–1962), German-Austrian Nazi Party official and convicted war criminal, a major organizer of the Holocaust

Adolf Hitler (1889–1945), German politician and leader of the Nazi Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei; NSDAP) (1900–1904)

Ernst Kaltenbrunner (1903–1946), Austrian SS official and convicted war criminal, a major organizer of the Holocaust (1913– )

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951), Austrian-British philosopher (1903–1906)

Early career

On the advice of family friend and local SS leader Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Eichmann joined the Austrian branch of the Nazi Party on 1 April 1932, member number 889,895.[19] His membership in the SS was confirmed seven months later (SS member number 45,326). His regiment was SS-Standarte 37, responsible for guarding the party headquarters in Linz and protecting party speakers at rallies, which would often become violent. Eichmann pursued party activities in Linz on weekends while continuing in his position at Vacuum Oil in Salzburg.

A few months after the Nazi seizure of power in Germany in January 1933, Eichmann lost his job due to staffing cutbacks at Vacuum Oil. The Nazi Party was banned in Austria around the same time. These events were factors in Eichmann's decision to return to Germany.

Like many other Nazis fleeing Austria in the spring of 1933, Eichmann left for Passau, where he joined Andreas Bolek at his headquarters. After he attended a training programme at the SS depot in Klosterlechfeld in August, Eichmann returned to the Passau border in September, where he was assigned to lead an eight-man SS liaison team to guide Austrian National Socialists into Germany and smuggle propaganda material from there into Austria. In late December, when this unit was dissolved, Eichmann was promoted to SS-Scharführer (squad leader, equivalent to corporal). Eichmann's battalion of the Deutschland Regiment was quartered at barracks next door to Dachau concentration camp.

On 21 March 1935 Eichmann married Veronika (Vera) Liebl (1909–1997). The couple had four sons: Klaus (born 1936 in Berlin), Horst Adolf (born 1940 in Vienna), Dieter Helmut (born 1942 in Prague) and Ricardo Francisco (born 1955 in Buenos Aires). Eichmann was promoted to SS-Hauptscharführer (head squad leader) in 1936 and was commissioned as an SS-Untersturmführer (second lieutenant) the following year.

In 1938, Eichmann was posted to Vienna to help organise Jewish emigration from Austria, which had just been integrated into the Reich through the Anschluss. Jewish community organisations were placed under supervision of the SD and tasked with encouraging and facilitating Jewish emigration. Funding came from money seized from other Jewish people and organisations, as well as donations from overseas, which were placed under SD control. Eichmann was promoted to SS-Obersturmführer (first lieutenant) in July 1938, and appointed to the Central Agency for Jewish Emigration in Vienna created in August in a room in the former Palais Albert Rothschild at Prinz-Eugen-Straße 20–22. By the time he left Vienna in May 1939, nearly 100,000 Jews had left Austria legally, and many more had been smuggled out to Palestine and elsewhere

World War II

Within weeks of the invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, Nazi policy toward the Jews changed from voluntary emigration to forced deportation. After discussions with Hitler in the preceding weeks, on 21 September SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, head of the SD, advised his staff that Jews were to be collected into cities in Poland with good rail links to facilitate their expulsion from territories controlled by Germany, starting with areas that had been incorporated into the Reich. He announced plans to create a reservation in the General Government (the portion of Poland not incorporated into the Reich), where Jews and others deemed undesirable would await further deportation. On 27 September 1939 the SD and the Sicherheitspolizei (SiPo, "Security Police") – the latter comprising the Geheime Staatspolizei (Gestapo) and Kriminalpolizei (Kripo) police agencies – were combined into the new Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA, "Reich Security Main Office"), which was placed under Heydrich's control.

After a posting in Prague to assist in setting up an emigration office there, Eichmann was transferred to Berlin in October 1939 to command the Reichszentrale für jüdische Auswanderung ("Reich Central Office for Jewish Emigration") for the entire Reich under Heydrich and Heinrich Müller, head of the Gestapo. He was immediately assigned to organise the deportation of 70,000 to 80,000 Jews from Ostrava district in Moravia and Katowice district in the recently annexed portion of Poland. On his own initiative, Eichmann also laid plans to deport Jews from Vienna.

On 19 December 1939, Eichmann was assigned to head RSHA Referat IV D4 (RSHA Sub-Department IV-D4), tasked with overseeing Jewish affairs and evacuation. Heydrich announced Eichmann to be his "special expert", in charge of arranging for all deportations into occupied Poland. The job entailed co-ordinating with police agencies for the physical removal of the Jews, dealing with their confiscated property, and arranging financing and transport. Within a few days of his appointment, Eichmann formulated a plan to deport 600,000 Jews into the General Government.

Open for a larger view

From the start of the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Einsatzgruppen (task forces) followed the army into conquered areas and rounded up and killed Jews, Comintern officials, and ranking members of the Communist Party.[66] Eichmann was one of the officials who received regular detailed reports of their activities. On 31 July, Göring gave Heydrich written authorisation to prepare and submit a plan for a "total solution of the Jewish question" in all territories under German control and to co-ordinate the participation of all involved government organisations. The Generalplan Ost (General Plan for the East) called for deporting the population of occupied Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union to Siberia, for use as slave labour or to be murdered.

Eichmann stated at his later interrogations that Heydrich told him in mid-September that Hitler had ordered that all Jews in German-controlled Europe were to be killed. "I never saw a written order," Eichmann said at his trial. "All I know is that Heydrich told me, 'the Führer ordered the physical extermination of the Jews.'" The initial plan was to implement Generalplan Ost after the conquest of the Soviet Union. However, with the entry of the United States into the war in December and the German failure in the Battle of Moscow, Hitler decided that the Jews of Europe were to be exterminated immediately rather than after the war, which now had no end in sight. Around this time, Eichmann was promoted to SS-Obersturmbannführer (lieutenant colonel), the highest rank he achieved.

To co-ordinate planning for the proposed genocide, Heydrich hosted the Wannsee Conference, which brought together administrative leaders of the Nazi regime on 20 January 1942. In preparation for the conference, Eichmann drafted for Heydrich a list of the numbers of Jews in various European countries and prepared statistics on emigration. Eichmann attended the conference, oversaw the stenographer who took the minutes, and prepared the official distributed record of the meeting. In his covering letter, Heydrich specified that Eichmann would act as his liaison with the departments involved. Under Eichmann's supervision, large-scale deportations began almost immediately to extermination camps at Bełżec, Sobibor, Treblinka and elsewhere. The genocide was code-named Operation Reinhard in honour of Heydrich, who had died in Prague in early June from wounds suffered in an assassination attempt. Kaltenbrunner succeeded Heydrich as head of the RSHA.

Eichmann did not make policy, but acted in an operational capacity. Specific deportation orders came from his RSHA superior, Gestapo chief Müller, acting on Himmler's behalf. Eichmann's office was responsible for collecting information on the Jews in each area, organising the seizure of their property, and arranging for and scheduling trains. His department was in constant contact with the Foreign Office, as Jews of conquered nations such as France could not as easily be stripped of their possessions and deported to their deaths.

House of the Wannsee Conference. January 20th 1942

Madagascar Project

Jews were concentrated into ghettos in major cities with the expectation that at some point they would be transported farther east or even overseas. Horrendous conditions in the ghettos – severe overcrowding, poor sanitation, and a lack of food – resulted in a high death rate. On 15 August 1940, Eichmann released a memorandum titled Reichssicherheitshauptamt: Madagaskar Projekt (Reich Security Main Office: Madagascar Project), calling for the resettlement to Madagascar of a million Jews per year for four years. When Germany failed to defeat the Royal Air Force in the Battle of Britain, the invasion of Britain was postponed indefinitely. As Britain still controlled the Atlantic and her merchant fleet would not be at Germany's disposal for use in evacuations, planning for the Madagascar proposal stalled. Hitler continued to mention the Plan until February 1942, when the idea was permanently shelved.

Hungarian woman and children arrive at Auschwitz-Birkenau, May or June 1944 (photo from the Auschwitz Album)

Germany invaded Hungary on 19 March 1944. Eichmann arrived the same day, and was soon joined by top members of his staff and five or six hundred members of the SD, SS, and SiPo. Hitler's appointment of a Hungarian government more amenable to the Nazis meant that the Hungarian Jews, who had remained essentially unharmed until that point, would now be deported to Auschwitz concentration camp to serve as forced labour or be gassed. Eichmann toured northeastern Hungary in the last week of April and visited Auschwitz in May to assess the preparations. During the Nuremberg Trials, Rudolf Höss, commandant of the Auschwitz concentration camp, testified that Himmler had told Höss to receive all operational instructions for the implementation of the Final Solution from Eichmann. Round-ups began on 16 April, and from 14 May, four trains of 3,000 Jews per day left Hungary and travelled to the camp at Auschwitz II-Birkenau, arriving along a newly built spur line that terminated a few hundred metres away from the gas chambers. Between 10 and 25 per cent of the people on each train were chosen as forced labourers; the rest were killed within hours of arrival. Under international pressure, the Hungarian government halted deportations on 6 July 1944, by which time over 437,000 of Hungary's 725,000 Jews had died. In spite of the orders to stop, Eichmann personally made arrangements for additional trains of victims to be sent to Auschwitz on 17 and 19 July. Throughout October and November, Eichmann arranged for tens of thousands of Jewish victims to be forced to march, in appalling conditions, from Budapest to Vienna, a distance of 210 kilometres.

On 24 December 1944, Eichmann fled Budapest just before the Soviets completed their encirclement of the capital. He returned to Berlin, where he arranged for the incriminating records of Department IV-B4 to be burned. Along with many other SS officers who fled in the closing months of the war, Eichmann and his family were living in relative safety in Austria when the war in Europe ended on 8 May 1945.

After World War II

At the end of the war, Eichmann was captured by US forces and spent time in several camps for SS officers using forged papers that identified him as Otto Eckmann. He escaped from a work detail at Cham, Germany, when he realised that his identity had been discovered. He obtained new identity papers with the name of Otto Heninger and relocated frequently over the next several months, moving ultimately to the Lüneburg Heath. He initially found work in the forestry industry and later leased a small plot of land in Altensalzkoth, where he lived until 1950. Meanwhile, former commandant of Auschwitz Rudolf Höss and others gave damning evidence about Eichmann at the Nuremberg trials of major war criminals starting in 1946.

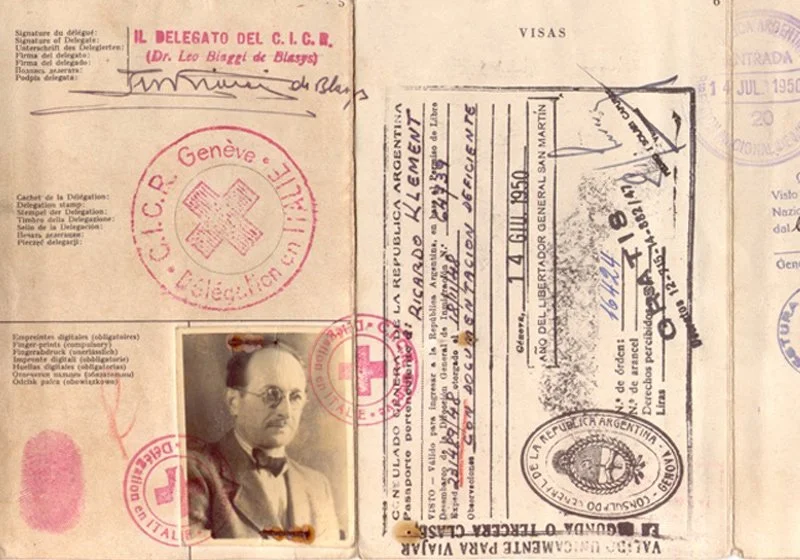

In 1948, Eichmann obtained a landing permit for Argentina and false identification under the name Ricardo Klement through an organisation directed by Bishop Alois Hudal, an Austrian cleric and Nazi sympathiser then residing in Italy. These documents enabled him to obtain an International Committee of the Red Cross humanitarian passport and the remaining entry permits in 1950 that would allow emigration to Argentina. He travelled across Europe, staying in a series of monasteries that had been set up as safe houses. He departed from Genoa by ship on 17 June 1950 and arrived in Buenos Aires on 14 July.

Argentina

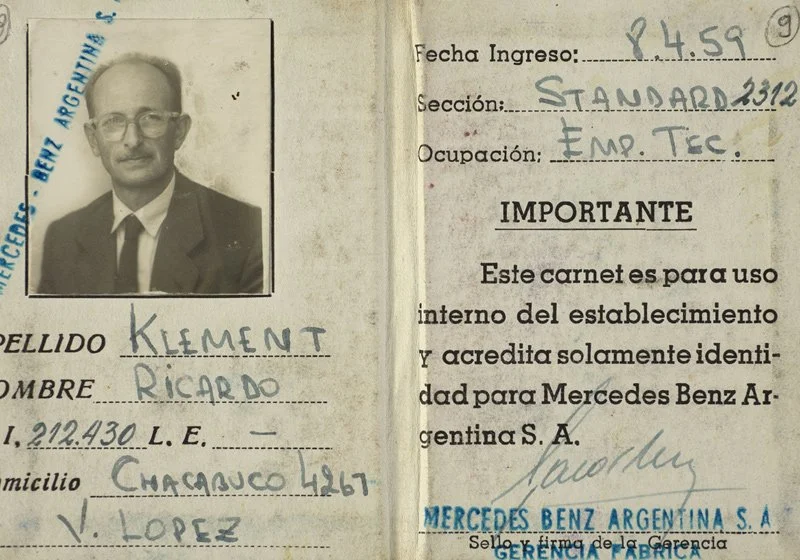

At this time, Argentina had become a safe haven for thousands of Nazi criminals who arrived by what was known as "the rat route." Going under his false name, Eichmann was employed at the Mercedes-Benz workshop. In 1952 his wife and children joined him.

Red Cross passport for "Ricardo Klement", used by Eichmann to enter Argentina in 1950

Eichmann's Argentinean worker's I.D. for Mercedes-Benz, issued in the name of Ricardo Klement

Giovanni C ship, aboard which Eichmann escaped to Argentina, 1950

A Wanted man

Eichmann's significant role as one of the architects of the "Final Solution" of Europe's Jews, began to emerge in the late forties. From the early fifties, rumors proliferated claiming that he was in South America, as the intelligence services of Western Germany and the United States had already learned with certainty. But it was thanks to the determination and persistence of a number of individuals resolved to expose the true identity of "Ricardo Klement," that agents of Israel's Mossad launched a hunt ending with Eichmann's capture on May 11 1960.

Fritz Bauer, the (Jewish) prosecutor-general of the West German state of Hessen, acting outside his formal role for fear that official action might foil the success of the operation, conveyed to the Israeli government solid information about Eichmann's whereabouts. Lothar Hermann, a German born Holocaust survivor who had emigrated to Argentina, prompted Mossad to take action on the basis of particularly credible information received from his daughter Sylvia, who had romantic ties to one of Eichmann's sons, Klaus. In addition, there was the vigorous activity of Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal, and of Mossad agent Manus Diamant, who came up with a portrait photograph of Eichmann from the war years. Each one in his own way prepared the path for Mossad to plan and execute the abduction operation.

Capturing Eichmann

The snatch team included: Rafi Eitan, Peter Malkin, Zvi Aharoni, and Moshe Tabor. The operation was carried out under the command of Mossad chief Isser Harel with the backing of Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion. After seizing Eichmann close to his Garibaldi street home in a suburb of Buenos Aires, his captors rushed him to a place of concealment. Under interrogation, Eichmann admitted his true identity and signed a document giving his consent to stand trial in Israel. Eleven days later he was clandestinely flown to Israel on an El Al airliner.

Panoramic surveillance photograph of Eichmann's house, Buenos Aires

Surveillance truck close to his house

Surveillance photograph of Eichmann taken by a private detective

El Al Brittania 4x plane, enabling direct flight from Argentina to Israel, 1960

Two days after Eichmann's arrival in Israel, on May 23, 1960, the Prime Minister took to the Knesset podium to proclaim that Eichmann had been captured and was in Israel. The news stunned and amazed public opinion in Israel and worldwide.

The months following the abduction were marked by a severe diplomatic row between Israel and Argentina, the latter complaining to the international community and the UN Security Council about infringement of its sovereignty. Feverish diplomatic efforts by Israel's foreign ministry and the Jewish intellectuals who rallied worldwide, restored bilateral relations to normalcy. In the course of the trial, particularly towards its conclusion, a majority of nations and world public opinion recognized the justice of the Israeli action, and Israel's right to bring the villain to justice.

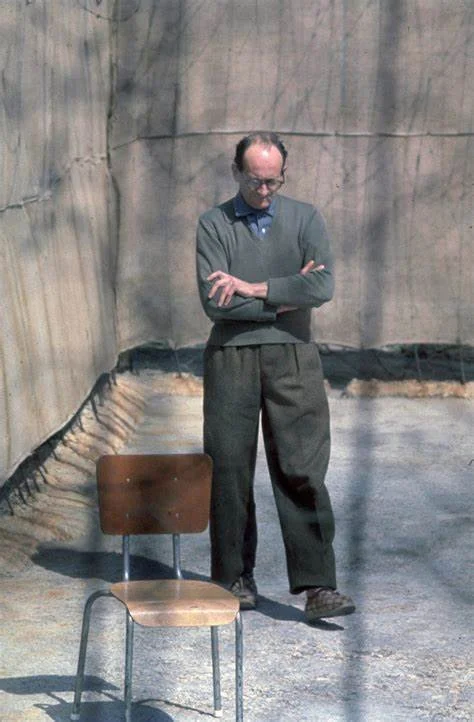

Eichmann awaiting trial in 1961

Personal belongings upon arrest in Israel, 1960

Eichmann's fingerprints upon arrest, 1960

The Trial

The Israeli government arranged for the trial to have prominent media coverage. Capital Cities Broadcasting Corporation of the United States obtained exclusive rights to videotape the proceedings for television broadcast. Many major newspapers from all over the globe sent reporters and published front-page coverage of the story. The trial was held at Beit Ha'am (today known as the Gerard Behar Center), an auditorium in central Jerusalem. Eichmann sat inside a bulletproof glass booth to protect him from assassination attempts. The building was modified to allow journalists to watch the trial on closed-circuit television, and 750 seats were available in the auditorium itself. Videotape was flown daily to the United States for broadcast the following day

The prosecution case was presented over the course of 56 days, involving hundreds of documents and 112 witnesses (many of them Holocaust survivors). Hausner (The chief prosecutor) ignored police recommendations to call only 30 witnesses; only 14 of the witnesses called had seen Eichmann during the war. Hausner's intention was to not only demonstrate Eichmann's guilt but to present material about the entire Holocaust, thus producing a comprehensive record. Hausner's opening address began, "It is not an individual that is in the dock at this historic trial and not the Nazi regime alone, but anti-Semitism throughout history."

Throughout his cross-examination, prosecutor Hausner attempted to get Eichmann to admit he was personally guilty, but no such confession was forthcoming. Eichmann admitted to not liking the Jews and viewing them as adversaries, but stated that he never thought their annihilation was justified. When Hausner produced evidence that Eichmann had stated in 1945 that "I will leap into my grave laughing because the feeling that I have five million human beings on my conscience is for me a source of extraordinary satisfaction", Eichmann said he meant "enemies of the Reich" such as the Soviets. During later examination by the judges, he admitted he meant the Jews, and said the remark was an accurate reflection of his opinion at the time.

The trial adjourned on 14 August, and the verdict was read on 12 December. Eichmann was convicted on 15 counts of crimes against humanity, war crimes, crimes against the Jewish people, and membership in a criminal organisation. The judges declared him not guilty of personally killing anyone and not guilty of overseeing and controlling the activities of the Einsatzgruppen. He was deemed responsible for the dreadful conditions on board the deportation trains and for obtaining Jews to fill those trains. In addition to being found guilty of crimes against Jews, he was convicted for crimes against Poles, Slovenes, and Roma. Moreover, Eichmann was found guilty of membership in three organisations that had been declared criminal at the Nuremberg trials: the Gestapo, the SD, and the SS. When considering the sentence, the judges concluded that Eichmann had not merely been following orders, but believed in the Nazi cause wholeheartedly and had been a key perpetrator of the genocide. On 15 December 1961, Eichmann was sentenced to death by hanging.

Eichmann's trial judges Benjamin Halevy, Moshe Landau, and Yitzhak Raveh

Eichmann on trial in Israel 1961

Eichmann was hanged at a prison in Ramla hours later. The hanging, scheduled for midnight at the end of 31 May, was slightly delayed and thus took place a few minutes past midnight on 1 June 1962.[5] The execution was attended by a small group of officials, four journalists and the Canadian clergyman William Lovell Hull, who had been Eichmann's spiritual counselor while in prison. His last words were reported to be:

Long live Germany. Long live Argentina. Long live Austria. These are the three countries with which I have been most connected and which I will not forget. I greet my wife, my family and my friends. I am ready. We'll meet again soon, as is the fate of all men. I die believing in God.

Rafi Eitan, who accompanied Eichmann to the hanging, claimed in 2014 to have heard him later mumble "I hope that all of you will follow me", making those his final words.

Within hours Eichmann's body had been cremated, and his ashes scattered in the Mediterranean Sea, outside Israeli territorial waters, by an Israeli Navy patrol boat.

Otto Adolf Eichmann

19 March 1906

Solingen, Rhine Province, Kingdom of Prussia, German Empire

Died 1 June 1962 (aged 56)

Ayalon Prison, Ramla, Israel

Adolf Eichmann - Murderer of Millions Documentary