The Angel of Death

SS physician Josef Mengele conducted inhumane, and often deadly, medical experiments on prisoners at Auschwitz. He became the most notorious of the Nazi doctors who conducted experiments at the camp. Mengele was nicknamed the "angel of death." He is often remembered for his presence on the selection ramp at Auschwitz.

Dr Josef Mengele

Josef Mengele was born on March 16, 1911, in the Bavarian city of Günzburg, Germany. He was the eldest son of Karl Mengele, a prosperous manufacturer of farming equipment.

Mengele studied medicine and physical anthropology at several universities. In 1935, he earned a PhD in physical anthropology from the University of Munich. In 1936, Mengele passed the state medical exams.

In 1937, Mengele began working at the Institute for Hereditary Biology and Racial Hygiene in Frankfurt, Germany. There, he was an assistant to the director, Dr. Otmar von Verschuer. Verschuer was a leading geneticist known for his research on twins. Under Verschuer’s direction, Mengele completed an additional doctorate in 1938.

'Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer with female twins observing eye color'

Embracing Nazi Ideology

Mengele did not actively support the Nazi Party before it came to power. However, in 1931, he joined the Stahlhelm, the paramilitary of another right-wing party, the German National People’s Party. Mengele became a member of the Nazi SA when it absorbed the Stahlhelm in 1933, but he ceased actively participating in it in 1934.

During his university studies, however, Mengele embraced racial science, the false theory of biological racism. He believed that Germans were biologically different from and superior to members of all other races. Racial science was a fundamental tenet of Nazi ideology. Hitler used racial science to justify the forced sterilization View This Term in the Glossary of persons with certain physical or mental diseases or physical deformities. The Nuremberg Race Laws, which outlawed marriage between Germans and Jewish, Black, or Romani peoples, were also based upon racial science.

In 1938, Mengele joined the Nazi Party and the SS. In his work as a scientist, he sought to support the Nazi goal of maintaining and increasing the supposed superiority of the German “race.” Mengele’s employer and mentor, Verschuer, also embraced biological racism. In addition to conducting research, Verschuer and his staff—including Mengele—provided expert opinions to Nazi authorities who had to determine whether persons qualified as German under the Nuremberg Laws. Mengele and his colleagues also evaluated Germans whose physical or mental condition might qualify them to be forcibly sterilized or barred from marriage under German law.

Serving on the Eastern Front

In June 1940, Mengele was drafted into the German army (Wehrmacht). A month later, he volunteered for the medical service of the Waffen-SS (the military branch of the SS). At first, he worked for the SS Race and Settlement Main Office (RuSHA) in German-occupied Poland. There, Mengele evaluated the criteria and methods used by the SS to determine whether persons claiming to be of German descent were racially and physically suitable to qualify as Germans.

Around the end of 1940, Mengele was assigned to the engineering battalion of the SS Division “Wiking” as a medical officer. For about 18 months beginning in June 1941, he saw extremely brutal fighting on the eastern front. In addition, in the first weeks of Germany’s attack on the Soviet Union, Mengele’s division slaughtered thousands of Jewish civilians. Mengele’s service on the eastern front earned him the Iron Cross, both 2nd and 1st Class, and promotion to SS captain (SS-Hauptsturmführer).

Mengele returned to Germany in January 1943. While awaiting his next Waffen-SS assignment, he began to work again for his mentor Verschuer. Verschuer had recently become the director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Genetics, and Eugenics (KWI-A) in Berlin.

Assigned to Auschwitz

On May 30, 1943, the SS assigned Mengele to Auschwitz. There is some evidence that Mengele himself requested this assignment. He worked as one of the camp physicians at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Auschwitz-Birkenau was the largest of the Auschwitz camps and also served as a killing center for Jews deported from throughout Europe. In addition to other duties, Mengele had responsibility for Birkenau's Zigeunerlager (literally, “Gypsy camp”). Beginning in 1943, nearly 21,000 Romani men, women, and children (pejoratively referred to as Zigeuner or “Gypsies”) were sent to Auschwitz and imprisoned in the Zigeunerlager. When this family camp was liquidated on August 2, 1944, Mengele participated in selecting the 2,893 Romani prisoners who were to be murdered in the Birkenau gas chambers. Shortly thereafter, he was appointed chief physician for the part of the Auschwitz camp complex called Auschwitz-Birkenau or Auschwitz II. In November 1944, he was assigned to the Birkenau hospital for the SS.

“Angel of Death”

As part of their camp duties, medical staff at Auschwitz performed so-called selections. The purpose of the selections was to identify persons who were unable to work. The SS considered such persons useless and therefore murdered them. When transports of Jews arrived at Birkenau, the camp medical personnel selected some of the able-bodied adults to perform forced labor in the concentration camp. Those not selected for labor, including children and older adults, were murdered in the gas chambers.

Camp physicians at Auschwitz and at other concentration camps also conducted periodic selections in the camp infirmaries and barracks. They conducted these selections in order to identify prisoners who were injured or had become too ill or weak to work. The SS used various methods to murder these prisoners, including lethal injections and gassing. Mengele routinely carried out such selections at Birkenau, leading some prisoners to refer to him as the “angel of death.”

Prisoner Gisella Perl, a Jewish gynecologist at Birkenau, later recalled how Mengele’s appearance in the women’s infirmary filled the prisoners with terror:

“We feared these visits more than anything else, because we never knew whether we would be permitted to live. He was free to do whatever he pleased with us”.

After World War II, Mengele became infamous for his work at Auschwitz thanks to the accounts of prisoner physicians who had worked under him and of prisoners who had survived his medical experiments.

Mengele was one of some 50 physicians who served at Auschwitz. He was neither the highest ranking doctor in the at Auschwitz camp complex nor the commander of the other doctors there. Nevertheless, his name is by far the best known of all the doctors who served at Auschwitz. One reason for this was Mengele’s frequent presence on the ramp where selections took place. When Mengele did not himself perform selection duty, he often still appeared at the ramp, looking among the prisoners for twins for his experiments and physicians for the Birkenau infirmary.

Separate from his regular duties at Auschwitz, Mengele conducted research and experiments on prisoners. His mentor Verschuer may even have arranged Mengele’s assignment to Auschwitz for the purpose of supporting the research of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Genetics, and Eugenics (KWI-A). Throughout his time at Auschwitz, Mengele sent his colleagues in Germany blood, body parts, organs, skeletons, and fetuses. These were all taken from Auschwitz prisoners. Mengele collaborated on his colleagues’ research projects by conducting studies and experiments for them using prisoners.

Mengele sought to identify specific physical and biochemical markers that could definitively identify the members of specific races. Mengele and his colleagues believed that finding such markers was vitally important for preserving the supposed racial superiority of the German people. For Mengele and his colleagues, the importance of the research justified conducting harmful and lethal experiments on people—in this case Auschwitz prisoners—whom they considered to be racially inferior.

Renate Guttmann

Renate, her twin brother, Rene, and their German-Jewish parents lived in Prague. Shortly before the twins were born, Renate's parents had fled Dresden, Germany, to escape the Nazi government's policies against Jews. Before leaving Germany to live in Czechoslovakia, Renate's father, Herbert, worked in the import-export business. Her mother, Ita, was an accountant.

1933-39: Renate's family lived in a six-story apartment building along the #22 trolley line in Prague. A long, steep flight of stairs led up to their apartment, where Renate and her brother, Rene, shared a crib in their parents' bedroom; a terrace overlooked the yard outside. Renate and Rene wore matching outfits and were always well-dressed. Their days were often spent playing in a nearby park. In March 1939 the German army occupied Prague.

1940-45: Just before Renate turned 6, her family was sent to Auschwitz from the Theresienstadt ghetto. There, she became #70917. She was separated from her brother and mother and taken to a hospital where she was measured and X-rayed; blood was taken from her neck. Once, she was strapped to a table and cut with a knife. She got injections that made her throw up and have diarrhea. While Renate was ill in the hospital after an injection, guards came in to take the sick to be killed. The nurse caring for her hid her under her long skirt and she was quiet until the guards left.

Renate and her brother survived and were reunited in America in 1950. They learned that as one pair of the "Mengele Twins," they had been used for medical experiments.

“They also gave us injections all over our bodies. As a result of these injections, my sister fell ill. Her neck swelled up as a result of a severe infection. They sent her to the hospital and operated on her without anesthetic in primitive conditions”

From the account of Lorenc Andreas Menasche, camp number A 12090.2

“Samples of blood were collected first from the fingers and then from the arteries, two or three times from the same victims in some cases. The children screamed and tried to cover themselves up to avoid being touched. The personnel resorted to force. (…) Drops were also put into their eyes….Some pairs of children received drops in both eyes, and others in only one. ….The results of these practices were painful for the victims. They suffered from severe swelling of the eyelids, a burning sensation”

[Mengele]”visited us as a good uncle, bringing us chocolate. Before applying the scalpel or a syringe, he would say: 'Don’t be afraid, nothing is going to happen to you…' ...he injected chemical substances, performed surgery on Tibi’s spine. After the experiments he would bring us gifts...In the course of later experiments, he had pins inserted into our heads. The puncture scars are still visible. One day he took Tibi away. My brother was gone for several days. When he was brought back, his head was all dressed in bandages. He died in my arms”.

Evading Justice

In January 1945, as the Soviet Red Army advanced through western Poland, Mengele fled Auschwitz with the rest of the camp’s SS personnel. He spent the next few months serving at the Gross-Rosen concentration camp and its subcamps. In the final days of the war, he donned a German army uniform and joined a military unit. After the war ended, the unit surrendered to US military forces.

Posing as a German army officer, Mengele became a US prisoner of war. The US Army released him in early August 1945, unaware that Mengele's name was already on a list of wanted war criminals.

From late 1945 until spring 1949, Mengele worked under a false name as a farmhand near Rosenheim, Bavaria. From here he was able to establish contact with his family. When US war crimes investigators learned of Mengele’s crimes at Auschwitz, they tried to find and arrest him. Based on lies told by Mengele’s family, however, the investigators concluded that Mengele was dead. The US effort to arrest him forced Mengele to recognize that he was not safe in Germany. With financial support from his family, Mengele immigrated to Argentina under yet another false name in July 1949.

By 1956, Mengele was well established in Argentina and felt so safe that he obtained Argentine citizenship as José Mengele. In 1959, however, he learned that West German prosecutors knew he was in Argentina and were seeking his arrest. Mengele immigrated to Paraguay and obtained citizenship there. In May 1960, Israeli intelligence agents abducted Adolf Eichmann in Argentina and took him to Israel to be tried. Correctly guessing that the Israelis were also looking for him, Mengele fled Paraguay. With support from his family in Germany, he spent the rest of his life under an assumed name near São Paulo, Brazil. On February 7, 1979, Mengele suffered a stroke and drowned while swimming at a vacation resort near Bertioga, Brazil. He was buried in a suburb of São Paulo under the assumed name “Wolfgang Gerhard.”

The Changing faces of Josef Mengele

In May 1985, the governments of Germany, Israel, and the United States agreed to cooperate in tracking down Mengele and bringing him to justice. German police raided the home of a Mengele family friend in Günzburg, Germany, and found evidence that Mengele had died and been buried near São Paulo. Brazilian police located Mengele's grave and exhumed his corpse in June 1985. American, Brazilian, and German forensic experts positively identified the remains as those of Josef Mengele. In 1992, DNA evidence confirmed this conclusion.

Mengele eluded arrest for 34 years and was never brought to justice.

Mengele's grave in São Paulo

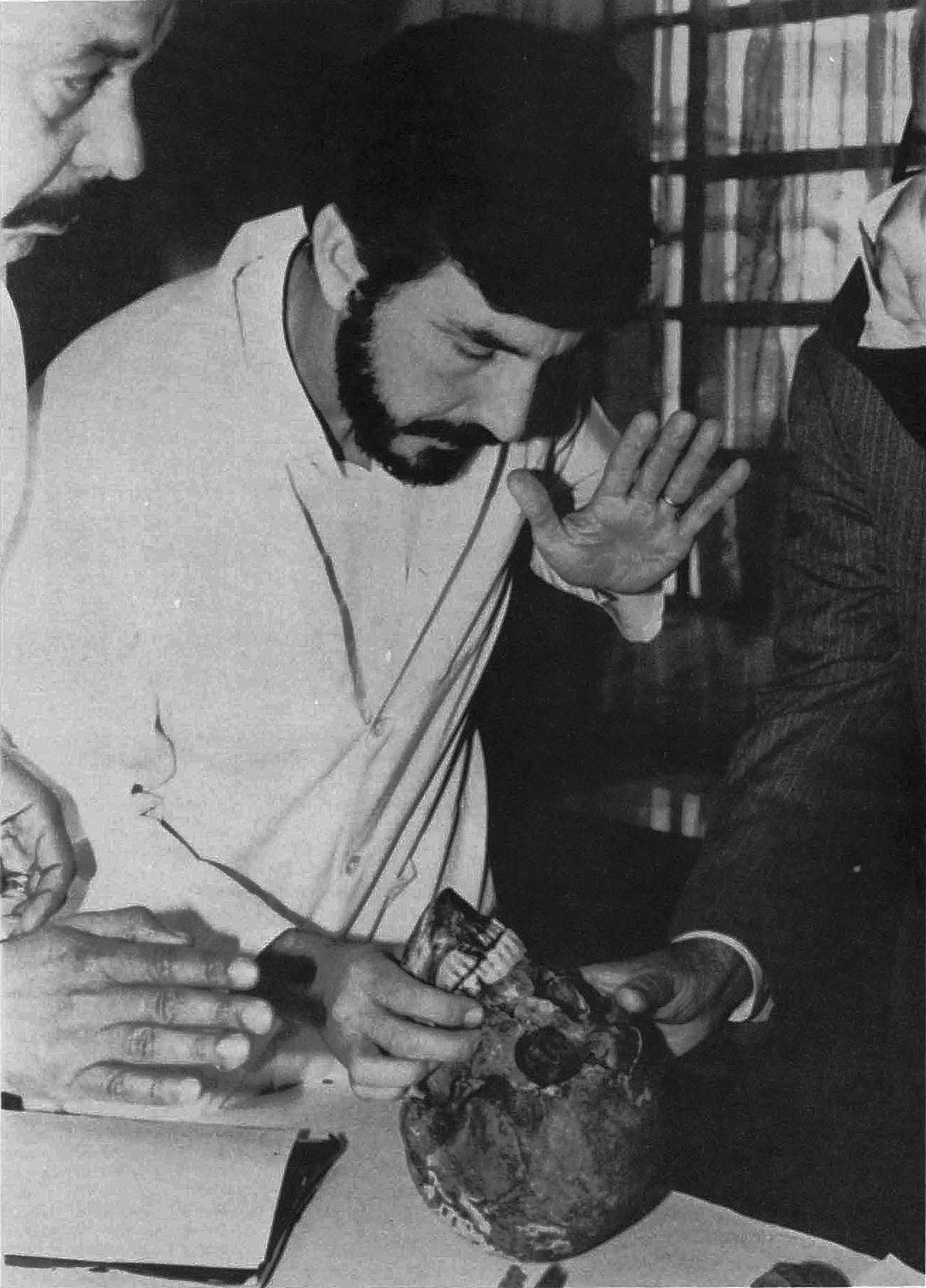

Forensic anthropologists examine Mengele's skull in 1986. The skeleton is stored at the São Paulo Institute for Forensic Medicine in Brazil

Born 16 March 1911

Günzburg, Kingdom of Bavaria, German Empire

Died7 February 1979 (aged 67)

South Atlantic Ocean, off Bertioga, Santos, São Paulo, Brazil

Josef Mengele - The Angel of Death Documentary