Martin

Bormann

Martin Ludwig Bormann was a German Nazi Party official and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery. He gained immense power by using his position as Adolf Hitler's private secretary to control the flow of information and access to Hitler. He used his position to create an extensive bureaucracy and involve himself as much as possible in the decision making.

Bormann joined a paramilitary Freikorps organisation in 1922 while working as manager of a large estate. He served nearly a year in prison as an accomplice to his friend Rudolf Höss (later commandant of Auschwitz concentration camp) in the murder of Walther Kadow. Bormann joined the Nazi Party in 1927 and the Schutzstaffel (SS) in 1937. He initially worked in the party's insurance service, and transferred in July 1933 to the office of Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess, where he served as chief of staff.

Bormann gained acceptance into Hitler's inner circle and accompanied him everywhere, providing briefings and summaries of events and requests. He began acting as Hitler's personal secretary on 12 August 1935. After Hess's solo flight to Britain on 10 May 1941 to seek peace negotiations with the British government, Bormann assumed Hess's former duties, with the title of Head of the Parteikanzlei (Party Chancellery). He had final approval over civil service appointments, reviewed and approved legislation, and by 1943 had de facto control over all domestic matters. Bormann was one of the leading proponents of the ongoing persecution of the Christian churches and favoured harsh treatment of Jews and Slavs in the areas conquered by Germany during World War II.

Bormann moved to Munich in October 1928, where he worked in the SA insurance office. Initially the Nazi Party provided coverage through insurance companies for members who were hurt or killed in the frequent violent skirmishes with members of other political parties. As insurance companies were unwilling to pay out claims for such activities, in 1930 Bormann set up the Hilfskasse der NSDAP (Nazi Party Auxiliary Fund), a benefits and relief fund directly administered by the party. Each party member was required to pay premiums and might receive compensation for injuries sustained while conducting party business. Payments out of the fund were made solely at Bormann's discretion. He began to gain a reputation as a financial expert, and many party members felt personally indebted to him after receiving benefits from the fund. In addition to its stated purpose, the fund was used as a last-resort source of funding for the Nazi Party, which was chronically short of money at that time. After the Nazi Party's success in the 1930 general election, where they won 107 seats, party membership grew dramatically. By 1932 the fund was collecting 3 million ℛ︁ℳ︁ per year.

Bormann also worked on the staff of the SA from 1928 to 1930, and while there he founded the National Socialist Automobile Corps, precursor to the National Socialist Motor Corps. The organisation was responsible for co-ordinating the donated use of motor vehicles belonging to party members, and later expanded to training members in automotive skills.

personal vehicle pennant of Martin Bormann

In 1935, Bormann was appointed as overseer of renovations at the Berghof, Hitler's property at Obersalzberg. In the early 1930s, Hitler bought the property, which he had been renting since 1925 as a vacation retreat. After he became chancellor, Hitler drew up plans for expansion and remodelling of the main house and put Bormann in charge of construction. Bormann commissioned the construction of barracks for the SS guards, roads and footpaths, garages for motor vehicles, a guesthouse, accommodation for staff, and other amenities. Retaining title in his own name, Bormann bought up adjacent farms until the entire complex covered 10 square kilometres (3.9 sq mi). Members of the inner circle built houses within the perimeter, beginning with Hermann Göring, Albert Speer, and Bormann himself. Bormann commissioned the building of the Kehlsteinhaus (Eagle's Nest), a tea house high above the Berghof, as a gift to Hitler on his fiftieth birthday (20 April 1939). Hitler seldom used the building, but Bormann liked to impress guests by taking them there.

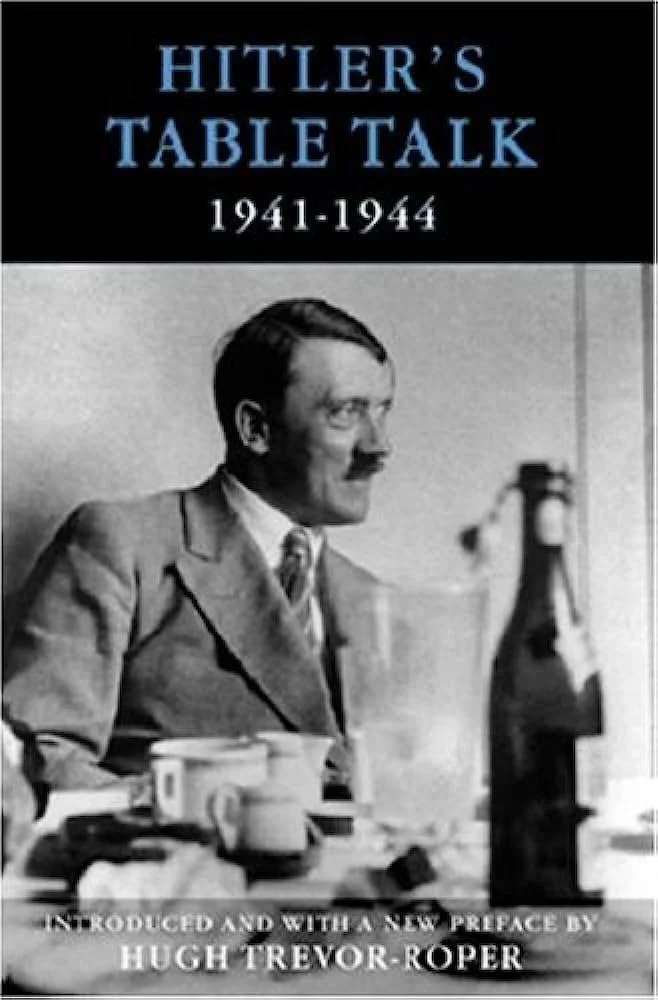

While Hitler was in residence at the Berghof, Bormann was constantly in attendance and acted as Hitler's personal secretary. In this capacity, he began to control the flow of information and access to Hitler. During this period, Hitler gave Bormann control of his personal finances. In addition to salaries as chancellor and president, Hitler's income included money raised through royalties collected on his book Mein Kampf and the use of his image on postage stamps. Bormann set up the Adolf Hitler Fund of German Trade and Industry, which collected money from German industrialists on Hitler's behalf. Some of the funds received through this programme were disbursed to various party leaders, but Bormann retained most of it for Hitler's personal use. Bormann and others took notes of Hitler's thoughts expressed over dinner and in monologues late into the night and preserved them. The material was published after the war as Hitler's Table Talk.

The Berghof

Table Talk

The Eagles Nest

During World War 2 Hitler was preoccupied with military matters and spending most of his time at his military headquarters on the eastern front, he came to rely more and more on Bormann to handle the domestic policies of the country. On 12 April 1943, Hitler officially appointed Bormann as Personal Secretary to the Führer. By this time Bormann had de facto control over all domestic matters, and this new appointment gave him the power to act in an official capacity in any matter.

Bormann was invariably the advocate of extremely harsh, radical measures when it came to the treatment of Jews, the conquered eastern peoples, and prisoners of war. He signed the decree of 31 May 1941 extending the 1935 Nuremberg Laws to the annexed territories of the East. Thereafter, he signed the decree of 9 October 1942 prescribing that the permanent Final Solution in Greater Germany could no longer be solved by emigration, but only by the use of "ruthless force in the special camps of the East", that is, extermination in Nazi death camps. A further decree, signed by Bormann on 1 July 1943, gave Adolf Eichmann absolute powers over Jews, who now came under the exclusive jurisdiction of the Gestapo. Historian Richard J. Evans estimates that 5.5 to 6 million Jews, representing two-thirds of the Jewish population of Europe, were exterminated by the Nazi regime in the course of The Holocaust.

During the later stages of the war Hitler transferred his headquarters to the Führerbunker ("Leader's bunker") in Berlin on 16 January 1945, where he (along with Bormann, his secretary Else Krüger, and others) remained until the end of April. The Führerbunker was located under the Reich Chancellery garden in the government district of the city centre. The Battle of Berlin, the final major Soviet offensive of the war, began on 16 April 1945. By 19 April, the Red Army started to encircle the city. On 20 April, his 56th birthday, Hitler made his last trip above ground. In the ruined garden of the Reich Chancellery, he awarded Iron Crosses to boy soldiers of the Hitler Youth. That afternoon, Berlin was bombarded by Soviet artillery for the first time.

In the early morning hours of 29 April 1945, Wilhelm Burgdorf, Goebbels, Hans Krebs, and Bormann witnessed and signed Hitler's last will and testament. In the will, Hitler described Bormann as "my most faithful Party comrade" and named him executor of the estate. That same night, Hitler married Eva Braun in a civil ceremony.

At around 11:00 pm on 1 May, Bormann left the Führerbunker with SS doctor Ludwig Stumpfegger, Hitler Youth leader Artur Axmann, and Hitler's pilot Hans Baur, part of one of the groups attempting to break out of the Soviet encirclement. Bormann carried with him a copy of Hitler's last will and testament. The group left the Führerbunker and travelled on foot via a U-Bahn subway tunnel to the Friedrichstraße station, where they surfaced. Several members of the party attempted to cross the Spree River at the Weidendammer Bridge while crouching behind a Tiger tank. The tank was hit by an anti-tank round and Bormann and Stumpfegger were knocked to the ground. Bormann, Stumpfegger, and several others eventually crossed the river on their third attempt. Bormann, Stumpfegger, and Axmann walked along the railway tracks to Lehrter station, where Axmann decided to leave the others and go in the opposite direction. When he encountered a Red Army patrol, Axmann doubled back. He saw two bodies, which he later identified as Bormann and Stumpfegger, on a bridge near the railway switching yard. He did not have time to check thoroughly, so he did not know how they died. Since the Soviets never admitted to finding Bormann's body, his fate remained in doubt for many years.

During the chaotic days after the war, contradictory reports arose as to Bormann's whereabouts. Sightings were reported in Argentina, Spain, and elsewhere. Bormann's wife was placed under surveillance in case he tried to contact her. Jakob Glas, Bormann's long-time chauffeur, insisted that he saw Bormann in Munich in July 1946. In case Bormann was still alive, multiple public notices about the upcoming Nuremberg trials were placed in newspapers and on the radio in October and November 1945 to notify him of the proceedings against him.

The trial got underway on 20 November 1945. Lacking evidence confirming Bormann's death, the International Military Tribunal tried him in absentia, as permitted under article 12 of their charter. He was charged with three counts: conspiracy to wage a war of aggression, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. The prosecution stated that Bormann participated in planning and co-signed virtually all of the antisemitic legislation put forward by the regime. Bormann was convicted of war crimes and crimes against humanity and acquitted of conspiracy to wage a war of aggression. On 15 October 1946, he was sentenced to death by hanging, with the provision that if he were later found alive, any new facts brought to light by that time could be taken into consideration to reduce or overturn the sentence

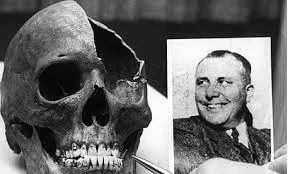

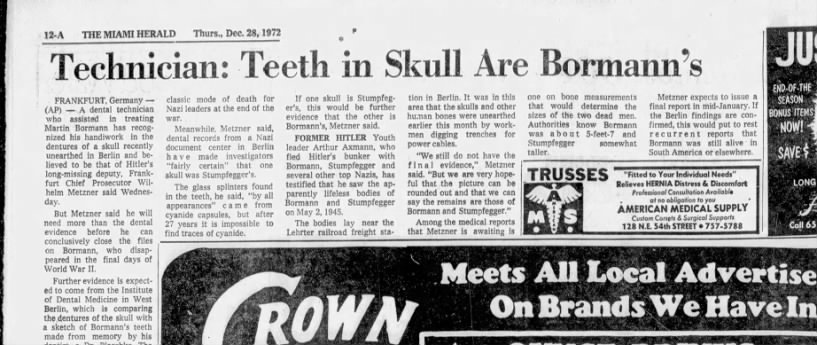

Excavations on 20–21 July 1965 at the site specified by Axmann failed to locate the bodies. However, on 7 December 1972, construction workers uncovered human remains near Lehrter station in West Berlin, only 12 m (39 ft) from the spot they were last seen. At the subsequent autopsies, fragments of glass were found in the jaws of both skeletons, suggesting that the men had committed suicide by biting cyanide capsules to avoid capture. Dental records reconstructed from memory in 1945 by Hugo Blaschke identified one skeleton as Bormann's, and damage to the collarbone was consistent with injuries that Bormann's sons reported he had sustained in a riding accident in 1939. Forensic examiners determined that the size of the skeleton and shape of the skull were identical to Bormann's. Likewise, the second skeleton was deemed to be Stumpfegger's, since it was of similar height to his last known proportions. Composite photographs, in which images of the skulls were overlaid on photographs of the men's faces, were completely congruent. Facial reconstruction was undertaken in early 1973 on both skulls to confirm the identities of the bodies. Soon afterward, the West German government declared Bormann dead. The family was not permitted to cremate the body, in case further forensic examination later proved necessary.

The remains were conclusively identified as Bormann's in 1998 when German authorities ordered genetic testing on fragments of the skull. The testing was led by Wolfgang Eisenmenger, Professor of Forensic Science at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. Tests using DNA from one of his relatives identified the skull as that of Bormann. Bormann's remains were cremated and his ashes were scattered over the Baltic Sea on 16 August 1999.

Martin Ludwig Bormann

Born

17th June 1900

Wegeleben, Prussia, German Empire

Died

2nd May 1945 (aged 44)

Berlin, Nazi Germany