Stolpersteine

Stumbling Stones

“Every stone has its story”

“You won’t fall, but if you stumble and look, you must bow down with your head and your heart.”

There are now more than 70,000 of these stones around the world, spanning 20 different languages. They can be found in 2,000-plus towns and cities across 24 countries, including Argentina, Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Russia, Slovenia and Ukraine. Together, they constitute the world’s largest decentralised memorial.

For all this international reach, the Stolpersteine are highly individual in form. The project’s motto is ‘one victim, one stone’, referencing a teaching in the Talmud, the book of Jewish law, that ‘a person is only forgotten when his or her name is forgotten’.

Each plaque’s inscription begins ‘HERE LIVED’ in the local language, followed by the individual’s name, date of birth and fate. For some, this is exile to another country. For others, it is suicide. For a few, it is liberation from a concentration camp. But for the vast majority, it is deportation and murder.

The project began in 1992, when Cologne-based artist Gunter Demnig first laid plaques in this format for Sinti and Roma victims of the Holocaust, who during that time were commonly referred to as ‘Gypsies’. He called the plaques ‘stumbling stones’ as a metaphor. “You won’t fall,” he recently told CNN. “But if you stumble and look, you must bow down with your head and your heart.”

For Demnig, the immediacy of each location – directly in front of a victim’s last known home – is critical to the memorial’s impact. “When people see the terror started in their city, their neighbourhood, maybe even in the house they are living in, it all becomes quite concrete,” he said in a recent interview with Deutsche Welle.

By 2005, the Stolpersteine project had expanded so much that Demnig could no longer both make and install each plaque. That’s when he asked Friedrichs-Friedländer to take on the production.

“I knew within five minutes we could work together,” Friedrichs-Friedländer said. “For me it is the strongest form of Holocaust memorial you can have. You bring the names back.”

For the last 14 years, Friedrichs-Friedländer has hand-engraved individual Holocaust fates onto small commemorative plaques called Stolpersteine, or ‘stumbling stones’. Each plaque is a 10cm brass square affixed on top of a cuboid concrete block that’s installed into the pavement directly before a Holocaust victim’s last known, voluntary residence.

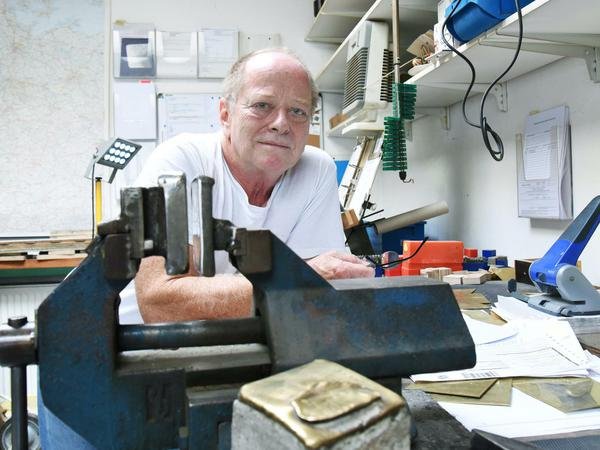

Friedrichs-Friedländer engraves each plaque by hand – stamp by stamp, letter by letter, fate after fate. Although there’s now a minimum nine-month waiting list for a Stolpersteine, he vehemently rejects mechanising the process.

“As soon as you bring in a mechanised element, it becomes anonymous,” he said.

To date, Friedrichs-Friedländer has engraved more than 63,000 Stolpersteine in more than 20 languages. The work is regularly traumatic. His eyes water as he describes a set of 34 stones for a former Jewish orphanage in Hamburg. The children were all between one and six years old.

“With the youngsters it always hits particularly hard,” he said.

As much as the plaques serve to commemorate individual lives, the Stolpersteine also trace the malign mechanics of deportation. Multiple stones in front of the same building show how the Gestapo returned to the same house again and again, splintering neighbours and family members along the routes to Treblinka, Theresienstadt, the Riga ghetto and Kaiserwald, and Auschwitz.

“I’ve done stones for families of 20 members,” said Friedrichs-Friedländer, “all sent in different directions, deported on different days.”

But when the Stolpersteine are laid before a building, “families are reunited,” he explained, brought back together in front of the home they once shared.

Gunter Demnig with two of his stones

Michael Friedrichs-Friedländer engraving in his workshop

The Stolpersteine also foster relationships between present-day residents of a building or street. The majority of stumbling stones are researched and funded by local neighbourhood initiatives.

Dietmar Schewe, a retired school principal in Berlin, recently coordinated a set of stumbling stones with his neighbours.

“It was really the first time our apartment building felt like a community” he said.

Likewise, the stumbling stones can reunite a victim’s surviving family members. Those who undertake the research required to produce a Stolpersteine must make contact with as many of the victim’s relatives as they can find – both to secure their approval and to invite them to the stone-laying ceremony.

For me it is the strongest form of Holocaust memorial you can have

Schewe welcomed 25 visitors from Israel to the Stolpersteine ceremony in front of his building.

“It was very harmonious, as well as very emotional,” he said. “We were able to show our visitors exactly which apartment their family members had lived in. It felt like a small but important encounter with the lived environment of their relatives.”

Friedrichs-Friedländer tells me of another installation ceremony in Cologne, where 34 relatives gathered from different countries around the world. “People have discovered relatives they never knew they had,” he said.

Such is the power of the Stolpersteine that a number of schools in the German-speaking world have now integrated the project into their curriculum, with students grouping together to research local Holocaust victims. It’s another important motivation for Friedrichs-Friedländer, who describes his own youth in Germany as a series of unanswered questions. “Teachers, parents... nobody wanted to tell you anything. It was as if the Third Reich never happened.”

The majority of Stolpersteine are researched and funded by local neighbourhood initiatives (Credit: dpa picture alliance/Alamy)

Since 1992, more than 70,000 Stolpersteine have been installed in 24 countries around the world (Credit: Sean O’Connor)

Friedrichs-Friedländer tries hard not to bring his work home with him, but it can be a struggle.

One must be present – one must suffer

“There are awful days when all I can do is cry,” he said. But the whole point of the Stolpersteine is their humanity – the emotional connection they require with the life and fate of each victim.

“One must be present. One must suffer,” Friedrichs-Friedländer continued. “If I ever get used to the work, if it ever becomes routine, I’ll stop.”

The Stumbling stones exhibition in Canada introduces the often unknown groundwork and manifold facets of the European art and remembrance project by artist Gunter Demnig. This short documentary places emphasis on the faces, names and stories behind every stone, interviewing Canadian Holocaust descendants about the importance of the Stumbling stones for their process of remembrance. The documentary was produced on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of the end of the Holocaust in May 2020.

"Tracks: Stumbling Stones Amsterdam" is a visually stunning journey, short documentary exploring the laying of “Stolpersteine” memorial stones honoring Holocaust victims, installed in front of the homes along the central canals in Amsterdam. A central theme of this film is the power and importance of remembrance. In the Jewish tradition, as long as a person is remembered they continue to live.

Click the Logo for more information on the Stolpersteine foundation

Adapted from the BBC website and originally written by By Eliza Apperly 29th March 2019