Karl Dönitz

Karl Dönitz (16 September 1891 – 24 December 1980) was a German admiral who briefly succeeded Adolf Hitler as head of state in May 1945, holding the position until the dissolution of the Flensburg Government following Germany's unconditional surrender to the Allies days later. As Supreme Commander of the Navy beginning in 1943, he played a major role in the naval history of World War II.

Early career and personal life

Dönitz was born in 1891 in Grünau, Germany. The son of middle class parents, Dönitz began his military career in 1910 when he enlisted in the German Imperial Navy. He received a commission in 1913 and requested a transfer to the burgeoning German submarine force in 1916. Dönitz took command of U-boat UB-68 in 1918. His time as a submarine captain did not last long, however. While operating in the Mediterranean, his submarine suffered technical malfunctions that forced it to the surface. Rather than let the U-boat fall into enemy hands, Dönitz scuttled the vessel and surrendered to the British. He spent the rest of the war in a British POW camp.

Oberleutnant zur See Karl Dönitz as Watch Officer of U-39 during World War I

On 27 May 1916, Dönitz married a nurse named Ingeborg Weber (1893–1962), the daughter of German general Erich Weber (1860–1933). They had three children whom they raised as Protestant Christians: daughter Ursula (1917–1990) and sons Klaus (1920–1944) and Peter (1922–1943). Both of Dönitz's sons were killed during the Second World War. Peter was killed on 19 May 1943 when U-954 was sunk in the North Atlantic with all hands.

Hitler had issued a policy stating that if a senior officer such as Dönitz lost a son in battle and had other sons in the military, the latter could withdraw from combat and return to civilian life. After Peter's death, Klaus was forbidden to have any combat role and was allowed to leave the military to begin studying to become a naval doctor. He returned to sea and was killed on 13 May 1944; he had persuaded his friends to let him go on the E-boat S-141 for a raid on Selsey on his 24th birthday. The boat was sunk by the French destroyer La Combattante.

After Dönitz returned to Germany, he chose to remain in the greatly reduced German navy. Under the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was forbidden to possess any submarines. Accordingly, Dönitz spent the next 15 years traveling the world aboard various German warships. Then in 1935, Admiral Erich Raeder chose Dönitz to reconstitute Germany’s submarine force in defiance of the Treaty of Versailles. As the wartime commander of Germany’s U-boats, Dönitz achieved enormous success destroying allied ships in the Atlantic. His command sank more than 3,500 allied vessels in the protracted Battle of the Atlantic during the course of World War II. with the German Navy lost approximately 784 submarines

Dönitz had only occasional contact with Hitler prior to 1943, but Dönitz met with the Führer twice a month after being named commander of the German navy. Even though Dönitz joined the Nazi party only in 1944, Hitler appreciated how Dönitz initiated a program of Nazi indoctrination for German sailors and Dönitz’s confidence that U-boats could still bring Britain to its knees. After July 1944, Hitler held Dönitz in even higher esteem when it was discovered that no German naval officers took part in the failed attempt to assassinate the Führer orchestrated by high-ranking Germany army officers. As Germany’s fortunes deteriorated, Dönitz remained steadfastly loyal to Hitler. The two men met with increasing frequency during the final months of the war, as Hitler became more and more isolated in his Berlin bunker. On the eve of the Soviet attack on the city, Dönitz ordered thousands of German sailors to take up arms and help defend the capital. On April 20, 1945, as Hitler celebrated his 56 birthday in his Führerbunker, more than a million Soviet soldiers began their assault on Berlin.

Commander-in-chief and Grand Admiral

Although Dönitz’s submarines were a serious threat to Britain’s survival, the German navy always rated behind the army and air force in German armament priorities. In 1943, just as the tide of the war turned decisively against Germany, Dönitz assumed command of the German Navy when Admiral Raeder retired. As German forces retreated on land, German U-Boats continued to menace allied ships through the end of the war.

Through 1944 and 1945, the Dönitz-initiated Operation Hannibal had the distinction of being the largest naval evacuation in history. The Baltic Fleet was presented with a mass of targets, the subsequent Soviet submarine Baltic Sea campaign in 1944 and Soviet naval Baltic Sea campaign in 1945 inflicted grievous losses during Hannibal. The most notable was the sinking of the MV Wilhelm Gustloff by a Soviet submarine. The liner had nearly 10,000 people on board. The evacuations continued after the surrender. From 3 to 9 May 1945, 81,000 of the 150,000 persons waiting on the Hel Peninsula were evacuated without loss. Albrecht Brandi, commander of the eastern Baltic, initiated a counter operation, the Gulf of Finland campaign, but failed to have an impact.

Adolf Hitler meets with Dönitz in the Führerbunker (1945).

President of Germany

Dönitz admired Hitler and was vocal about the qualities he perceived in Hitler's leadership. In August 1943, he praised his foresightedness and confidence; "anyone who thinks he can do better than the Führer is stupid." Dönitz's relationship with Hitler strengthened through to the end of the war, particularly after the 20 July plot, for the naval staff officers were not involved; when news of it came there was indignation in the OKM. Even after the war, Dönitz said he could never have joined the conspirators. Dönitz tried to imbue Nazi ideas among his officers, though the indoctrination of the naval officer corps was not the brainchild of Dönitz, but rather a continuation of the Nazification of the navy begun under his predecessor Raeder. Naval officers were required to attend a five-day education course in Nazi ideology. Dönitz's loyalty to him and the cause was rewarded by Hitler, who, owing to Dönitz's leadership, never felt abandoned by the navy. In gratitude, Hitler appointed the navy's commander as his successor before he committed suicide.

On 1 May, the day after Hitler's own suicide, Goebbels committed suicide. Dönitz thus became the sole representative of the collapsing German Reich. On 2 May, the new government of the Reich fled to Flensburg-Mürwik; Dönitz remained there until his arrest on 23 May 1945. That night, 2 May, Dönitz made a nationwide radio address in which he announced Hitler's death and said the war would continue in the East "to save Germany from destruction by the advancing Bolshevik enemy."

At 9:16 PM on the 30th January 1945 the Gustloff was hit by three torpedoes and proceeded to sink over the course of one hour. The ship was carrying lifeboats and rafts for 5,000 people, but many of the lifesaving appliances were frozen to the deck, and their effective use was further impeded by the fact that one of the torpedoes had hit the crew quarters, killing those best trained to deal with the situation. Nine vessels took on survivors throughout the night. Of the estimated 10,000 people on board the Gustloff, only 1,239 could be registered as survivors, making this the sinking with the highest death toll in maritime history.

MV Wilhelm Gustloff

Unconditional Surrender

As Germany’s military situation deteriorated, Dönitz attempted to negotiate a favorable surrender with the western allies in order to avoid abandoning German soldiers and equipment to the Soviet Union. Dönitz knew that Soviet captivity would likely mean death for hundreds of thousands of German soldiers. But Hitler had sealed these soldiers’ fates years earlier by insisting on a policy of no retreat. Dönitz had endorsed this decision not only by supporting Hitler but by ordering German sailors to face Soviet tanks in Berlin.

Now, Germany’s rapid collapse prevented Dönitz’s attempts to control events. German commanders who felt no personal loyalty to Dönitz began surrendering in the west. The mass surrenders of the German 12th Army and parts of the 9th Army gave Dönitz hope, however, that he could negotiate a partial peace with the United States and Great Britain. Dönitz attempted to use occupied Denmark and Norway as bargaining chips in these efforts. American General Dwight Eisenhower and British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery refused these overtures and demanded the unconditional surrender of all German forces. Still, Dönitz urged German forces to keep fighting, and even upheld Hitler’s directive to destroy German infrastructure until May 6.

When Dönitz learned of Eisenhower’s insistence on a simultaneous German surrender on all fronts without the destruction of ships or airplanes, the German leader regarded it as unacceptable. From Dönitz’s headquarters in the town of Flensburg on the Danish border, he instructed his lieutenants to cable Eisenhower that a complete capitulation was impossible but a capitulation in the west would be immediately accepted. Eisenhower held steadfast in his resolve and threatened to resume bombing raids and close borders to those fleeing from the east if Dönitz did not sign a surrender on May 7. Only when Dönitz was faced with this threat of consigning all German soldiers outside American lines to Soviet captivity did he finally agree to surrender.

Karl Dönitz (centre, in long, dark coat) followed by Albert Speer (bareheaded) and Alfred Jodl (on Speer's right) during the arrest of the Flensburg government by British troops

Albert Speer, Dönitz, and Alfred Jodl

At the Nuremberg trials, Dönitz claimed the statement about the "poison of Jewry" was regarding "the endurance, the power to endure, of the people, as it was composed, could be better preserved than if there were Jewish elements in the nation." Later, during the Nuremberg trials, Dönitz claimed to know nothing about the extermination of Jews and declared that nobody among "my men thought about violence against Jews." Dönitz told Leon Goldensohn, an American psychiatrist at Nuremberg, "I never had any idea of the goings-on as far as Jews were concerned. Hitler said each man should take care of his business and mine was U-boats and the Navy." After the war, Dönitz tried to hide his knowledge of the Holocaust. He was present at the October 1943 Posen Conference where Himmler described the mass murder of Jews with the intent of making the audience complicit in this crime. It cannot be proven beyond doubt that he was present during Himmler's segment of the conference, which openly discussed the murder of European Jews.

Even after the Nuremberg Trials, with the crimes of the Nazi state well-known, Dönitz remained an antisemite. In April 1953, he told Speer that if it was the choice of the Americans and not the Jews, he would have been released.

Nuremberg Trials

Following the war, Dönitz was held as a prisoner of war by the Allies. He was indicted as a major war criminal at the Nuremberg Trials on three counts. One: conspiracy to commit crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Two: planning, initiating, and waging wars of aggression. Three: crimes against the laws of war. Dönitz was found not guilty on count one of the indictment, but guilty on counts two and three.

Dönitz was imprisoned for 10 years in Spandau Prison in what was then West Berlin. During his period in prison he was unrepentant, and maintained that he had done nothing wrong. He also rejected Speer's attempts to persuade him to end his devotion to Hitler and accept responsibility for the wrongs the German Government had committed. Conversely, over 100 senior Allied officers sent letters to Dönitz conveying their disappointment over the unfairness and verdict of his trial.

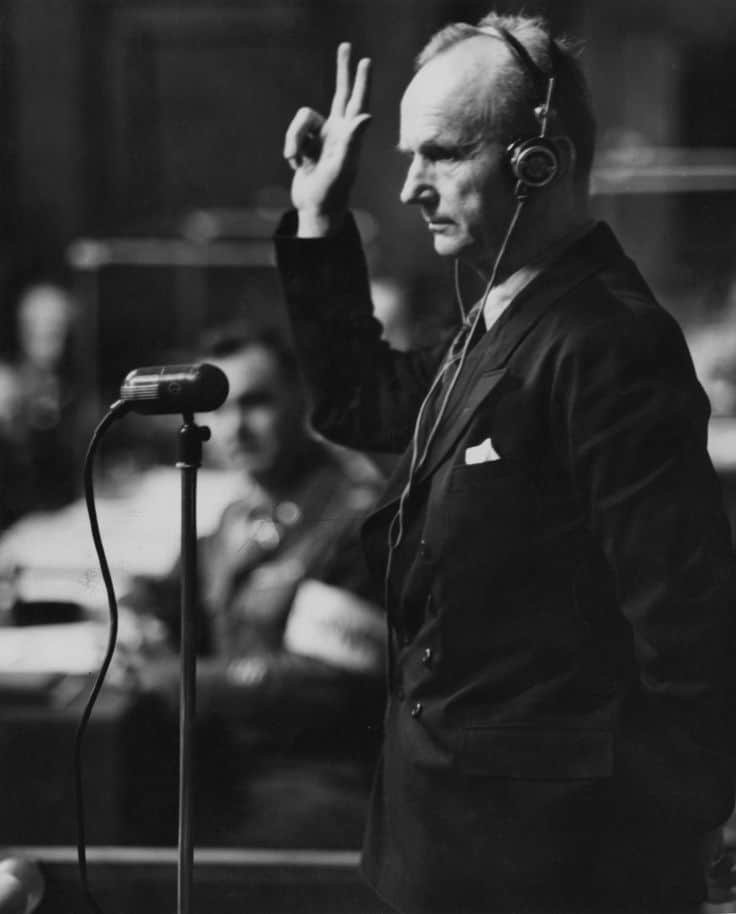

On the stand at Nuremberg

Donitz’s Nuremberg Detention report

Dönitz was unrepentant regarding his role in World War II, saying that he had acted at all times out of duty to his nation. He lived out the rest of his life in relative obscurity in Aumühle, occasionally corresponding with collectors of German naval history, and died there of a heart attack on Christmas Eve 1980 at the age of 89. As the last German officer with the rank of Großadmiral (grand admiral), he was honoured by many former servicemen and foreign naval officers who came to pay their respects at his funeral on 6 January 1981. He was buried in Waldfriedhof Cemetery in Aumühle without military honours, and service members were not allowed to wear uniforms to the funeral. Also in attendance were over 100 holders of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross.

Grave in Aumühle, east of Hamburg

Karl Dönitz - Commander of the Wolfpack Documentary

Born 16 September 1891

Grünau, Brandenburg, Prussia, German Empire

Died24 December 1980 (aged 89)

Aumühle, Schleswig-Holstein, West Germany