Operation Anthropoid: The Assassination of Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Heydrich, The Butcher Of Prague

In September 1941, Nazi leader Reinhard Heydrich replaced the man who had been in charge of governing Bohemia and Moravia, two Nazi-occupied provinces of Czechoslovakia.

His predecessor was Konstantin von Neurath, a high-ranking Nazi who, in the two years of his tenure, had overseen the implementation of the Nuremberg laws, the dismantling of the free press, and the abolition of political parties and trade unions. He had also sent some 1,200 student protestors to concentration camps and executed nine of them.

But Neurath, a man sentenced at the Nuremberg trials to 15 years in prison for war crimes, was too lenient for Adolf Hitler and the other Nazi leaders, which was why they were sending in Reinhard Heydrich.

Their hope was that Heydrich would be able to crush the Czech resistance to German occupation and get Czech motor and arms production for the German war effort back on track. Heydrich had their full confidence — he had already been responsible for some of the greatest atrocities of World War II.

He had organized Kristallnacht, the 1938 pogrom that destroyed the lives and livelihoods of thousands of Jewish citizens in Nazi Germany, and founded the SD, the security organization designed to crush resistance to Nazi rule. Hitler called Reinhard Heydrich “the man with the iron heart.”

The Czech people had different names for him. They called him “the Hangman” and “The Butcher of Prague” — epithets that still seem mild in comparison to what he did.

Within a week of taking power in Bohemia and Moravia, Heydrich declared martial law and ordered nearly 150 Czech resistance fighters executed.

In five months, somewhere between 4,000 and 5,000 citizens had been arrested; ten percent of them were executed before Heydrich had been in power for six months.

Most of those not sent to the firing squad were put on trains to concentration camps, where conditions were so poor that only four percent of prisoners would live to see the Allies declare victory.

Any effort at rebellion was met with harsh reprisals, and it wasn’t long before the Czech resistance had come to a grinding halt. But worse was still to come.

Heydrich’s ultimate goal was not to simply co-opt the Czech citizenry for use in German factories; the Nazi leaders had no interest in integrating the Czech people in the German Reich. When the war was over, the vast majority of the populace was to be exiled to Russia or murdered to clear the land for the growing German population.

When Heydrich was charged with the implementation of Hitler’s Final Solution, the murder of the entire Jewish population, it was clear to both the Allies and the exiled Czechoslovak government in Britain that Heydrich must be stopped at all costs.

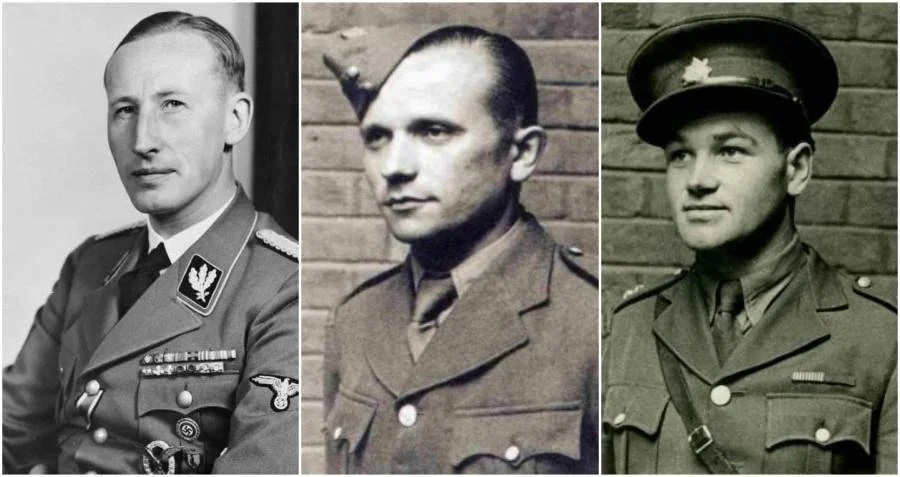

Reinhard Heydrich in 1934.

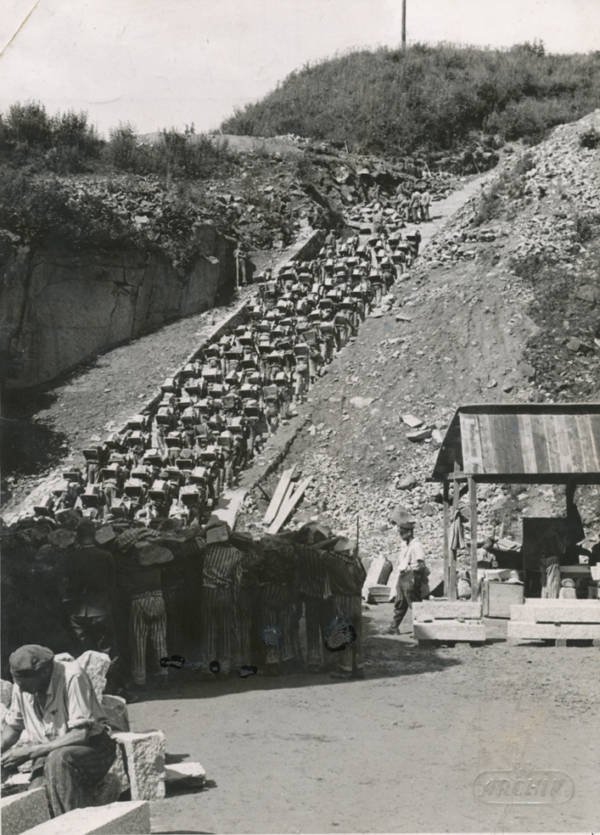

Many Czech prisoners were sent to the Mauthausen-Gusen death camp in Austria. Prisoners in the quarry (Stairs of Death) were forced to carry giant granite boulders in pointless forced labour.

Operation Anthropoid: The Assassination of Reinhard Heydrich

In October 1941, František Moravec, the exiled head of Czech intelligence, went to British Special Operations Executive, Winston Churchill’s famous “Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare,” to propose an assassination.

They agreed, and the project was given the codename Operation Anthropoid. The exiled Czech government wanted the assassins to be Czech or Slovak; they wanted to show their people that they hadn’t given up the fight, though they knew reprisals would be terrible.

Twenty-four Czech soldiers — part of a force of 2,000 exiled in Britain — were chosen for the mission and sent to train in Scotland.

The two most successful soldiers were selected and the mission’s date was set for October 28 — but from that point on, almost nothing went right.

One of the men selected for the mission was injured in training, and a replacement had to be named, which entailed new training and further delays. Finally, Jozef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš boarded a plane bound for Pilsen, an area west of Prague — but a navigation error sent them to Nehvizdy.

They then made their way overland to Prague, where they met up with their contacts and explained the plan. Their connections were horrified and did their best to explain the situation on the ground: any attempt on the life of a Nazi leader would have unthinkable consequences.

But Edvard Beneš, the exiled Czech president, was desperate to relight the dying fire of Czech resistance and felt only a dramatic blow would do. He urged his men to continue with the plan despite the danger of reprisals.

Left to right: Reinhard Heydrich, Jozef Gabčík, Jan Kubiš

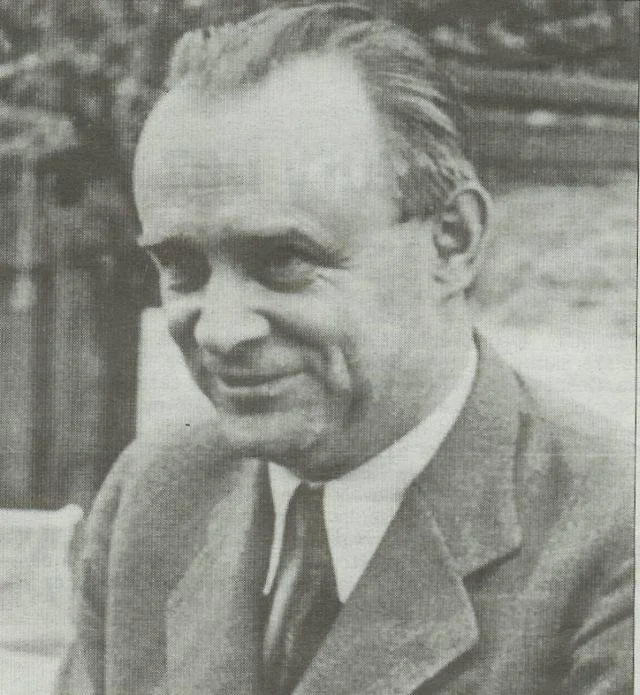

František Moravec, the officer of Czechoslovak Military Intelligence who proposed Operation Anthropoid. 1952.

Czech President Edvard Beneš allegedly encouraged Operation Anthropoid, even as locals on the ground warned him about the danger to his people.

Jozef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš boarded a plane bound for Pilsen, an area west of Prague — but a navigation error sent them to Nehvizdy.

A Missed Chance And A Dramatic Chase On The Streets Of Prague

It was lucky for Gabčík and Kubiš that Reinhard Heydrich, always aware of his own importance and the figure he cut on the streets of Prague, rode to work in an open-topped car.

On May 27, at 10:30 a.m., he began his commute, and Operation Anthropoid went into effect. Aided by a lookout, the assassins waited for him just behind a sharp curve in the road, where they anticipated that his car would have to slow.

There, they were right — but it was the last accurate prediction they would make that day. As the car approached, Gabčík stepped into the road and opened fire. But nothing happened — his gun had jammed.

The assassins thought Heydrich, having witnessed the attempt on his life, would hit the gas and make a run for it. But he instead pulled out his own gun and ordered his driver to slam on the breaks.

Kubiš, seeing that his companion was in mortal danger, threw a grenade into the back of the car and was himself caught in the explosion. Neither managed to see what happened, but the next thing they knew, Heydrich was outside of the car with a pistol leveled at Kubiš.

The firefight that ensued was chaotic. Kubiš fled on a bicycle with Reinhard Heydrich in pursuit. The driver chased after Gabčík, who managed to duck into a butcher shop, wound the driver with a well-placed shot, and escape on a tram. Kubiš got away when Heydrich, flagging quickly from a thigh wound, fell behind.

They were both certain they had lost their chance to kill Heydrich. Particularly devastating was the knowledge that the consequences of a failed assassination attempt would be as terrible for the Czech people as a successful one — but now they would have to contend with the wrath of the Butcher of Prague himself.

But luck was on the Allies’ side in the following weeks. Gabčík and Kubiš knew they hadn’t landed a shot — but what they didn’t realize was that the explosion had.

The force of the blast had driven shrapnel into Heydrich with devastating force. By the time the Nazi leader reached the hospital, he had a collapsed lung, a fractured rib, a torn diaphragm, and a ruptured spleen.

Despite his wounds, doctors initially thought the stout Heydrich might recover — until he collapsed several days later over lunch and went into a coma. He never woke, and the autopsy blamed sepsis — a malfunction in the body’s response to infection.

Reinhard Heydrich’s car after the Operation Anthropoid attack. 1942.

A Sten submachine gun like the one that jammed on Gabčík. These weapons were notorious among Czech soldiers for misfiring.

The Horrifying Consequences Of Operation Anthropoid

Adolf Hitler’s fury on learning of the attempt on Heydrich’s life was terrible. Reports say that he initially wanted to execute 10,000 Czechs in retaliation, and only his generals’ fear that reducing the population would harm the region’s ability to produce arms for the Germans swayed him.

What really happened was hardly better. 13,000 were arrested and sent to concentration camps, which was in many cases hardly different from execution. Death just took longer. In the end, scholars estimate that some 5,000 perished as a result of Heydrich’s assassination.

The village of Lidice fell under suspicion because several members of the exiled Czech military had been born there, as did the village of Ležáky, where the assassins had left a radio transmitter on their way through town. Inhabitants were murdered or sent to concentration camps, and the villages were burned to the ground.

The Germans let it be known that such retaliation would continue until the assassins were found. With threats, torture, and more bloodshed, they eventually achieved their aim.

They found Kubiš and his accomplices in the loft of a church and killed them in a firefight. Gabčík and his team hid in a crypt, which the Germans flooded with tear gas and water. The assassin and his accomplices committed suicide.

The church’s leaders were tortured and executed by firing squad, and the assassins’ heads were mounted on spikes.

The outraged world watched, and the Allies dissolved the Munich Agreement, the contract that had given the Germans Czechoslovakia — when the war was over, if the Allies won, the Czechs would be their own masters once again.

Though Heydrich’s replacements continued his work, some believe that if Heydrich had lived, the losses suffered would be have been much greater than they were.

But the Allies never attempted an assassination like Operation Anthropoid again during the war — the cost was simply too great.

My Photos of Operation Anthropoid

Area where the action Assassination took place

Prague Gestapo building

St Cyrus Church. Hideout, Gunfight and Flooded Cellar

Lidice - The aftermath, the Annihilation of a Village

The Movies

The man with the iron heart - trailer

Operation Anthropoid - trailer