The Russians are coming!

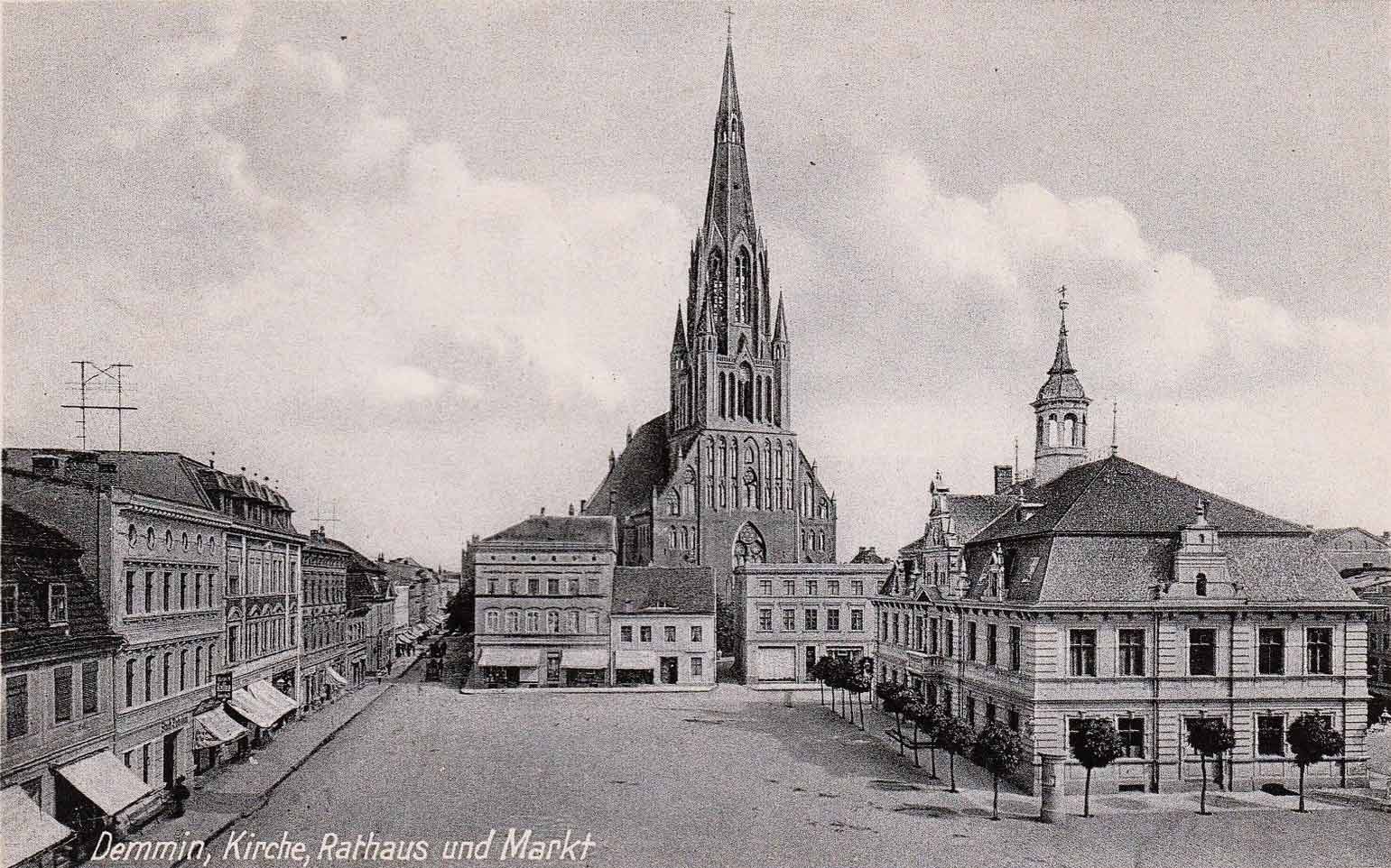

Demmin

In one German town, 1,000 people killed themselves in 72 hours

Soviet soldiers discovered a family of Nazi suicide victims in April, 1945. Thousand of Germans took their own lives in advance of the Red Army invasion. (Voller Ernst/Getty)

By April of 1945, both sides knew who was going to lose the Second World War. The Nazis could no longer hold back the enemy, and those active Allies — largely American, British, and Soviet troops — enjoyed a constellation of victories across the face of the soon-to-be defeated Third Reich. These soldiers took over towns, liberated prisoners, and in the case of the Red Army often terrorized civilians.

In the face of this prospect, thousands of Germans chose suicide over occupation. Not only was this a preferred method among high-ranking officials like Himmler, Goebbels, and Hitler — selbstmord (meaning “self-murder” in German)—was the avenue taken by many civilians as well. And perhaps there is no example of this more stark than what happened in the German city of Demmin in the days between April 30th and May 2nd, 1945.

Demmin, a modest town of about 16,000 people in the Pomerania region, was far from insulated from the anti-Semitism and furor that fueled Nazism. In the 1920s and 1930s, the area was a stronghold for the rising wave of nationalist right-wing parties. During the Weimar years, citizens of Demmin boycotted Jewish businesses, and in 1938, they sold the city’s only synagogue to a furniture company. Jews, unsurprisingly, moved elsewhere. The more fortunate ones left before the city’s virulent participation in Kristallnacht the year before the war began.

Numerous German cities experienced mass suicides at the end of the war. Over the conflict’s chaotic and desperate final months, Berlin witnessed around 7,000 people take their lives. But in terms of sudden and gruesome panic, it is hard to beat the heights of the Horrors at Demmin, a disaster in which an estimated 1,000 people took their lives, in a span scarcely longer than 72 hours.

Part of what made Demmin vulnerable was its geography. The city is surrounded by rivers, so when the Nazis destroyed the bridges to stall the advance of the Soviets, they trapped the city’s residents at the same time.

Anticipating the approach of the Soviets, Demmin’s residents hung white flags from its buildings in surrender. Still, a few bold members of the town aimed fire when the army entered the city. One teacher killed his wife and daughter before shooting an anti-tank grenade at the Red Army, then killing himself. Around noon, the first Soviet soldier was shot dead by a self-appointed militiaman, possibly this same teacher, further incensing the army as they advanced.

The real atrocities began in the evening, right around the time German citizens caught radio broadcasts of a parcel of news that did not bode well for the future of Nazi Germany: Adolf Hitler was dead, having taken his life that afternoon. Soon, Soviets began breaking into houses for loot, taking jewelry, heirlooms, and whatever else they found valuable. They broke into the city’s significant stores of alcohol, which emboldened their crimes. Later, they began taking gasoline and incinerating buildings. In just three days, 80% of the city’s structures were damaged or destroyed.

Yet perhaps the most terrorizing tactic of the invading Red Army was rape. At the twilight of the war, Demmin was but one of dozens of German cities traumatized by sexual assault, a condition that contributed severely to this lethal and widespread public panic.

The suicides themselves took a number of forms, and civilians exploited whatever they could get their hands on and whatever was nearby. People hanged themselves, slit their wrists, shot themselves and their family members, and ingested poison. Some jumped into the water to drown. A few who plunged into the Rivers Peene and Tollanse or who went to hang themselves from trees were thwarted by the Red Army, who retrieved them or cut their ropes.

A chilling aspect of the deaths and suicides in Demmin is how they happened at the level of the family and the household. The city’s official catalog of the event, which accounts for only 500 of the total people dead, recorded one boy who perished from being “strangled by grandfather.” Mothers drowned their children. Sons and daughters and elderly parents alike persuaded female family members who had been assaulted not to kill themselves. Like many atrocities of the era, many who were children at the time have begun to speak up about it in recent years, like Norbert Buske, whose mother was raped. He wrote a pamphlet called the End of the War in Demmin 1945. Another woman later found out that her mother, from whom she was separated at the time of the panic, had killed her two siblings.

Nazi propaganda encouraged suicide toward the end of the war, with the Party’s newspaper Völkischer Beobachter extolling the “pleasure of sacrificing personal existence” for the Fatherland. After the last concert at the Berlin Philharmonic on April 12, 1945, members of the Hitler Youth held baskets from which they passed cyanide capsules to the audience.

Suicide became a national trend, exercised by over 10,000 people.

And like in a cult, the mass suicides in Nazi Germany were in part a response to the shock of seeing a massive, inextricable lie come crashing down.

Demmin, enclosed by the Peene river in the north and west, and the Tollense river in the south. The bridges were blown up by the retreating Wehrmacht, the Red Army approached the town from the east.

A Nazi general on trial for warcrimes estimates the size of the cyanide capsules used by senior leaders to commit suicide. (Bettmann/Getty)

A peacful day in Demmin, The mass graves and Suicides of the locals.

The Horrors of Demmin

Not every suicide attempt was completed. Some mothers who had drowned their children were unable to drown themselves thereafter. In other cases, doses of poison proved to be lethal for children, but not for their mothers. There were also cases where children survived attempted drownings. Some members who survived a first attempt at suicide killed themselves by other methods. A mother and her repeatedly raped daughter, for instance, died by hanging themselves in an attic, after repeatedly failing to drown themselves in the Peene river. Another mother who had poisoned and buried three of her four children before, tried to hang herself on an oak three times, only to be prevented from doing so each time by Soviet soldiers. There are further records of Soviet soldiers preventing suicides by retrieving people from the river and nursing cut wrists. In another case, a grandfather forcibly took away a razor blade from a mother who was about to kill her children and herself after being raped by Soviet soldiers and hearing of the death of her husband. After Soviet soldiers had raped a girl to death and shot her father, an aunt cut her daughter's and son's wrists as well as her own. The other women of the family committed suicide, only one aunt was able to save the grandmother. One family survived, because the 15-year-old son persuaded his mother, one of the rape victims, to save herself, when she was already being dragged by the Tollense river.

Demmin's current chronicler, Gisela Zimmer, then 14 years old, recalls:

My mother was also raped. And then, together with us and with neighbors, she hurried towards the Tollense river, resolutely prepared to jump into it. My siblings realized only much later that I had held her back, that I had pulled her out of what may be called a state of trance, to prevent her from jumping into the water. There were people. There was screaming. The people were prepared to die. Children were told: 'Do you want to live on? The town is burning. These and those are dead already. No, we do not want to live any more.' And so, people went mostly into the rivers. That made the Russians feel creepy, too. There are examples where Russians, too, tried to pull people out or hinder them. But these hundreds of people, they were unable to withhold. And the population here was extremely panicked.

Zimmer writes that many of the dead were buried in mass graves on the Bartholomäi graveyard. Some were buried in individual graves at relatives' request. Others went unburied, as their bodies were not retrieved from the rivers. More than 900 bodies were buried in the mass graves; 500 of them were recorded on pages of a warehouse accountant's book converted into a death register. Weeks after the mass suicide, bodies still floated in the rivers. Clothing and other belongings of the drowned formed a border along the rivers' banks, up to 2 metres (6.6 ft) wide.

Click the picture to Watch More

Read the book - The extraordinary German bestseller on the final days of the Third Reich

One of the least understood stories of the Third Reich is that of the extraordinary wave of suicides, carried out not just by much of the Nazi leadership, but also by thousands of ordinary Germans, during in the war's closing period. Some of these were provoked by straightforward terror in the face of advancing Soviet troops or by personal guilt, but many could not be explained in such relatively straightforward terms.

Florian Huber's remarkable book, a bestseller in Germany, confronts this terrible phenomenon. Other countries have suffered defeat, but not responded in the same way. What drove whole families, who in many cases had already withstood years of deprivation, aerial bombing and deaths in battle, to do this?

In a brilliantly written, thoughtful and original work, Huber sees the entire project of the Third Reich as a sequence of almost overwhelming emotions and scenes for many Germans. He describes some of the key events which shaped the period from the First World War to the end of the Second, showing how the sheer intensity, allure and ferocity of Hitler's regime swept along millions. Its sudden end was, for many of them, simply impossible to absorb.

Promise Me You'll Shoot Yourself: The Downfall of Ordinary Germans, 1945